Thomas William Renton (1832/4 -1920): An Early Hamiltonian from Scotland

Thomas William’s Family History

Thomas Renton has a story. And, like everyone else, his story has meaning.

We speak today of being “upwardly mobile”, but Thomas was the personification of this concept more than a century ago.

As we will read, Thomas came from very humble origins. He was the son of an agricultural labourer in the borderlands of Scotland, eventually becoming a respected and prominent citizen in his adopted country. We will likely never discover what prompted him to migrate to Canada in the 1850s, but Hamilton Ontario is where he found his destiny. He was witness to the beginning of Canadian Confederation and saw Hamilton’s march of progress from a backwater town to a vibrant and progressive city, rivaling that of Chicago and other major American centres.

His life in Canada was both eventful and, at times, likely prosaic. He witnessed war first-hand, participated in the growing and important industry of the railway, and he lived through several personal tragedies. He was extremely proud of his children, going out of his way to document their accomplishments. He had a large family, and his numerous descendants (in Canada, in the United States, and even as far afield as Africa), can claim him as their own.

So, let’s dive into Thomas’ story.

Thomas’ parents were Robert Renton and Isabella (variously spelled Isabel, Isabelle, or Isobel) Fair. Records indicate that Robert was born in Edinburgh in 1811 on Calton Street.

There is only brief documentation on his mother, Isabella. She was born in Sprouston, Roxburghshire, Scotland on July 23, 1809.

At some point, Robert found himself in Westruther, Berwickshire, Scotland on June 17, 1832 where he married the delightfully surnamed Isabella Fair.

Thomas’ birthdate is consistently given as August 18, but the year varies. Some records say 1833, others 1834 — perhaps to circumvent the possibility that Isabella was pregnant at the time of her marriage. Most records seem to give 1832 as his actual year of birth.

After the marriage records from 1832, the couple next appear in the 1841 Scotland census[1]. Young Thomas is eight years old, the eldest of five siblings (Janet[2] age six, born in Stichill; Jean age four, born in Stichill [who dies in 1908]; and the seven-month-old twins Isabel and Helen, born in Berwick [who also dies in 1908]). Prior to the census, Robert would have had a younger brother named Robert. This child was born sometime in July 1836, but died on January 4, 1836.

Father, Robert, is an “agricultural labourer” and the family lives in Spottiswoode Eagle Lodge. In addition to those surnamed “Renton”, a 12-year-old girl named Helen Wanless is also living among them, and she is listed as an “agricultural labourer”

“Eagle Lodge” was the name used during Thomas’ lifetime. The two buildings, built in 1796, now called East and West Clock lodges, both flanked the entrance to Spottiswood House. Thomas almost certainly lived in what is now called the West Clock Lodge on the “Scottish Side” of the manor.

Spottiswoode is of historical note because of Alicia Ann Spottiswoode. She grew up in the manor and was later to become Lady John Scott (1810-1900). She was deeply interested in promoting Scottish culture, history, language and was likely the writer of a more refined version of the famous song “Annie Laurie”. She grew up in the Manor and was born and died there.

It is more than likely that Thomas would have known Lady Scott during his childhood and early adult years. And, given her interest in all things Scottish, it is quite possible that she would have called on Thomas’ family to ask about traditions and songs.

“Haud [hold] fast by the past” was Alicia’s motto. Who knows if that motto resonated with young Thomas?

The only other family living in another nearby Lodge was a young couple (also agricultural labourers), Andrew and Ann Scott (ages 29 and 30 respectively) with their three-year-old daughter Isabel and a one-year-old infant Margaret. Neighbours Andrew and Ann were the same ages as Thomas’ parents Robert and Isabel.

While Thomas lived in Westruther, the area was diminishing in population. Just before he was born in 1831 the population was estimated to be 830, almost the same in1841 at 829, and by 1851 it had slipped to 791 individuals.

Unlike the village, come 1851, the family had grown. Three more siblings were born in Berwick: George born in 1845 and who died in 1859, Elisabeth born in 1847 and who died in 1918, and William born in 1850.

Thomas, however, is no longer living with the family. An 18-year-old, he was now living in Blainslie[3], Roxburghshire, in the household of an 81-year-old woman named Margaret Scott. Within this household lived Margaret’s 54-year-old daughter, Agnes, her 46-year-old son William, and her 67-year- old sister Jane Dickson. Thomas gives his occupation as that of an apprentice joiner.

A joiner was a little different from a carpenter. At that time, a joiner would have been involved in using timber to create structures that would have been used in a building: things such as staircases, windows, doors, and furniture. A carpenter would have done similar work, but on-site, whereas a joiner would typically work in a shop setting.

One wonders if there was a family connection with his old neighbours at Eagle Lodge.

Meanwhile, by 1861, Thomas has a few new siblings: Alexander born in 1858, Andrew in 1856, Jane in 1852, and Mary in 1854.

It is unlikely Thomas met his little brothers Alexander, Andrew and his newest sister Jane. Around 1852-1853 Thomas left for Canada.

His mother, Isabella, would be dead by May 1865. His father, Robert, leaves this world in January 1890.

It is unlikely that Thomas ever saw his Scottish family again.

Thomas Settles in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada – mid 1850s

Thomas was part of a massive migration of immigrants from Scotland to Canada. Encouraged by the British government, Scots from the lowlands decided to leave their homelands and venture off to various provinces in Canada. In fact, between 1815 and 1870 roughly 170,000 Scots crossed the Atlantic and represented about 14% of British migration to Canada. At this time, rather than settle in the Maritime colonies as previous immigrants from the Highlands had done, this Lowland and Borderland group went to the Province of Canada (Ontario or Upper Canada as it was called then). By 1871, out of every 1000 Canadians, 157 were Scottish.

Most were farmers and tradespeople, but many were business professionals, teachers, and clergymen. These newcomers were predominantly Presbyterian.

Looking back, it appears that the prime motivator in immigration from the Lowlands was economic. Severe economic depression, with low wages, poor housing and unemployment occurred in the late 1840s and early 1850s — exactly around the time Thomas made his decision.

It is likely we will never know why Thomas chose to leave Scotland, and why go to Canada in particular. It may be that he heard stories from nearby families who had relatives in Canada, or perhaps he was influenced by the encouragement of government officials. Perhaps he knew people who read reports such as “Views and Canada and the Colonists”, published in Edinburgh in 1851 by James Brown[4]. In it Hamilton is generously described as being “handsome” and boasting steamboats and stages connecting to all other important towns with a railway being built, and prosperity everywhere you looked.

There does not appear to be any record of Thomas’ voyage to Canada, but typically one would have travelled overland to Edinburgh and depart (usually early in March) for Liverpool. Arriving there about 15 days later, a traveller would have embarked for New York City (likely arriving at the beginning of May). From there, the journey would have continued with another vessel travelling up the Hudson River, through the Erie Canal. Then, finally, around mid to end May, the traveller would cross over into Canada at Niagara Falls.

Assuming Thomas embarked at Liverpool, one wonders what was going through his mind. Was he excited? Filled with apprehensions? When the ship pulled away from the dock, did he gaily wave at those on the pier, even though he may not have had anyone there he knew? Did he grip the railing and stare at the shores of a land he would likely never see again? Or did he resolutely turn his gaze outward towards the sea, towards a new land of promise and adventure?

It is assumed that Thomas went to Hamilton directly from Scotland and did not settle elsewhere.

The land, the people, and the climate would have been far different from where Thomas had grown up. Both colder and hotter than the Borderlands, the highest temperature ever recorded in Hamilton was a sultry 41.1 °C (105.6 °F) on July 14, 1868. The coldest was -30.6 °C (-23.1 °F) on January 25, 1884. Thomas would have seen snow back home in Scotland, but likely never the amounts that would routinely fall on Hamilton during a typical winter.

It was an interesting choice. The city had only recently been incorporated in 1846 and at that time had a population of roughly 6830.

The growing city was hit by a smallpox epidemic a few years before Thomas’ arrival. The aftereffects of that event would surely have been in the minds of the population, especially since a new hospital was created directly because of the disaster.

Thomas arrived in what was quickly becoming a bustling city. In 1846, at the time of incorporation, there were many roads leading into the city from various communities, and there were both stagecoach and steamboat services to Toronto, Queenston, and Niagara. Eleven cargo schooners were owned in the city and an equal number of churches were providing spiritual guidance to the inhabitants. The city had a public reading room which gave citizens a place to access and read newspapers from other Canadian cities as well as from the United States and Europe.

This was no backwater village. Hamilton had shops offering all sorts of goods. It had four banking establishments. Tradesmen of all sorts lived there. There were sixty-five (!!) taverns with three breweries. A thriving import trade existed with ten importers of dry goods and groceries, and five importers of hardware. There were two tanneries, three coachmakers, and a marble and a stone works.

By 1855 the Grand Lodge of Canada opened its impressive building. The West Flamboro Methodist Church was constructed in 1879 (and was later purchased by the Dufferin Masonic Lodge in 1893). A public library was built and opened in 1890 and a department store named “Right House” was doing business in 1893.

Jumping ahead a little further, Hamilton boasted the first commercial telephone service in Canada – in fact, it was the first telephone exchange in all the enormous British Empire. It was the second exchange in North America, dating from 1877-1878. The city streets had urban electric street cars and two incline cars.

More significantly to Thomas, in November 1853, the first train on the 43-mile leg of the Great Western line, from Suspension Bridge to Hamilton, arrived. No doubt, given Thomas’ later career choices, this would have been a memorable event for him.

In 1860 the city began a beautification program to make the downtown core a “place of beauty as well as a place of commerce”. Things progressed nicely until 1862 when the City of Hamilton declared bankruptcy. People began to leave, and tenants abandoned their rental properties. Even the streetlights were no longer used by a desperate city trying to save money. The water in the Gore Park Fountain, so happily built during the beautification project of two years prior, was turned off to save on water pumping costs. Eventually the city began to reach some financial stability, and the lights came back on — but only until midnight!

And, in the midst of this economic chaos, Thomas married.

Thomas Marries — July 5th, 1862

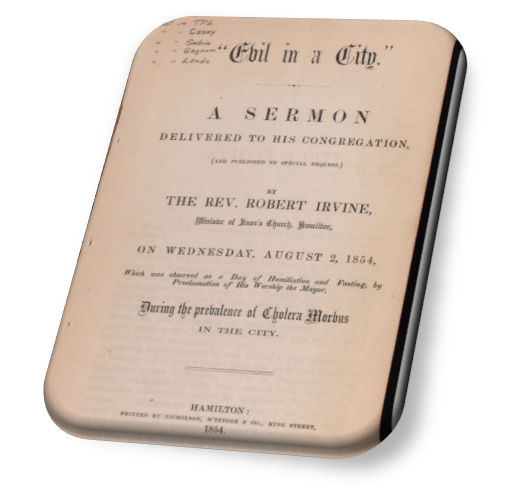

In the midst of the city’s dire financial crisis, on Saturday, July 5th, 1862, the 30-year-old Thomas married Miss Mary Ann McLeod. They were wed in the manse of Knox’s Church, with Robert Irvine D.D. officiating.

Robert Irvine was the Reverend of the Presbyterian “Free” Church, and he published many of his sermons and memoirs. Below is a sample of his work published in 1853 which exemplifies the tone of his preaching.

Mary Ann McLeod was the daughter of William Campbell McLeod. Thomas’ father-in-law was born in Farr, Scotland around 1815. His profession was that of a boilermaker. According to some online genealogies, William had gone to Quebec with a work crew in 1842 with the goal of building the first bridge over the St. Laurence River, then went to Hamilton in 1853. At some unspecified later date he ventured off to join the California Gold Rush, lost a great deal of money, and went back to Glasgow to return to his primary profession.

Although there may be some truth to the family lore, it is unlikely he went bridge-building in Quebec in 1842. The first bridge over the St. Laurence River, the Victoria Bridge, was erected between 1854 and 1859. The California Gold Rush took place between 1848-1855, further throwing off the suggested timeline. There is however a record of a William McLeod arriving in Quebec in 1842, but there is no certainty that that person was Mary Ann’s father.

It does not appear that William returned to Scotland after leaving it for Canada. William is documented in Dundee, Angus in 1851. He then appears in the Canadian census at Hamilton in 1861 as a boilermaker. In 1871, he is a widower, working as a boilermaker in Hamilton. In 1881, still a widower, he is living in Hamilton with the family of another married daughter. He eventually died there on January 8th, 1889.

Thomas’s mother-in-law, Mary McKay (or MacKay) was also born in Farr and married William in September 1833. She has proven quite elusive, and no other concrete information seems available other than her death in Hamilton on March 28, 1866.

Thomas and Mary Ann had twelve children together:

- Mary, born April 11, 1863

- Isabella Fair, born September 18, 1864

- William McLeod, born March 20, 1866

- Robert, born December 26, 1868

- Elizabeth Tindill Lizzie, born in August 1869, possibly premature (or, less likely, in 1872)

- Thomas, born 10 February 1871 and who died on February 18, just 8 days later

- George, born June 21, 1872, and who died March 23, 1873

- Jane, twin of George and who died August 13, 1882

- Georgina, born January 23, 1881

- Fleming Fair, born September 5, 1881

- Norman McLeod, born November 21, 1884

- Innes (or Ennis) Myrtle, born January 24, 1887

It is worth noting that Mary Ann was almost continuously pregnant from late 1862 to early 1872. No children were born for another ten years. Then, from 1881 through 1887 she had another four children, and given the dates, her penultimate child was likely born premature.

Military Involvement in the Fenian Raids

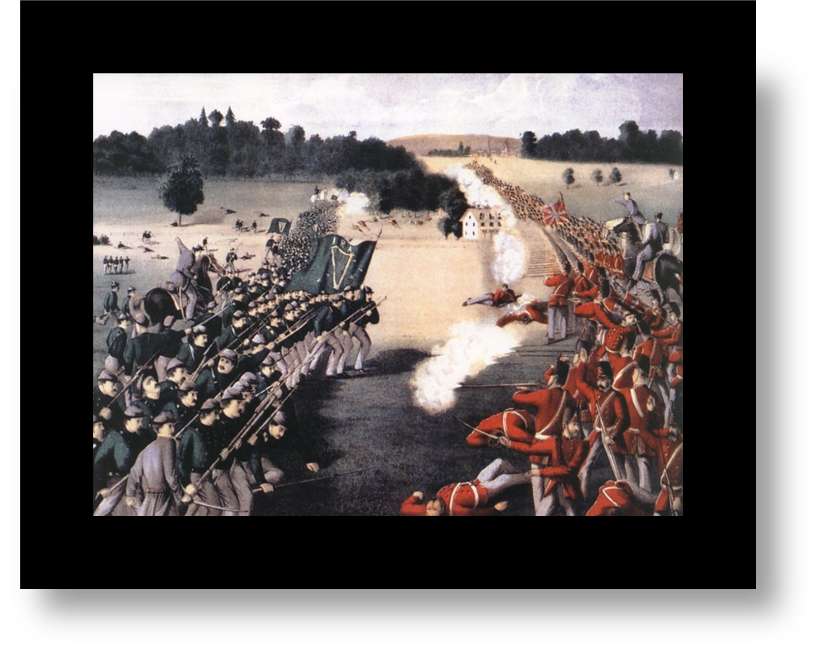

Briefly, the Fenians were a secret society of Irish patriots and had come from Ireland to the United States. Some Fenians wanted to take Canadian territories by force and essentially offer it up to the British in exchange for Irish independence. Several attacks occurred from around 1866 to 1871, and, for the most part, the Canadian military was woefully unprepared and disorganized.

Still, the Fenians did not prevail. However, their legacy may have played a part in the push for the Confederation of Canada, once Canada began to be concerned over potential threats of American military and economics strengths.

According to various sources (sadly none were properly documented), Thomas was part of the Hamilton Field Battalion (or the 11th Field Regiment). As a gunner[5], he was reputed to have been the first of the company to fire a shot, although there is no clarity around which battle he was involved in. It is possible that he was active in the Battle of Ridgeway fought nearby in 1866, and he may have been under the command of Lieut. Col. Booker, but this is all speculation.

In any case, the Hamilton Field Battalion was a voluntary militia (as were most at the time in Canada West). From what meagre records exist, they seemed to have spent much time marching in “shining” uniforms, doing field exercises, and gathering in public venues to regale the Hamilton public with speeches, poetry readings, light dramatic performances, musical interludes and honouring one another for military prowess.

Thomas may have truly seen action. He may have been the one to recount tales of battle to his family, friends, and associates. His military actions may have been retold by friends and family. In any case, according to several obituaries, Thomas had strongly felt opinions on military issues (thought precisely what they might have been is unknown).

Thomas and the Grand Trunk Railway

During Thomas’ lifetime, the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada was the major railroad in the Province of Canada (Ontario and Quebec). It connected Toronto to Montreal and at a later date it would be part of the Canadian National Railways, providing transportation across all of Canada.

Often abbreviated as the “GTR”, it had been incorporated in 1852, and it was then that the much-needed rail service was built to connect Toronto to Montreal. At the time of Confederation, in 1867, it was the largest railway system in the world, with 2055 km of track. By the late 1880s it was a massive concern, running from Sarnia to Portland Maine without interruption.

Despite its unflagging march of progress, it also had several headline making accidents. On 29 June 1864, one of their trains plunged off the Beloeil Bridge into the Richelieu River, killing 99 people.

Later, on 15 September 1885, the entire world learned about the GTR when Jumbo, the famous circus elephant, supposedly charged one of its trains near St. Thomas, Ontario and was killed. Some accounts state that the elephant charged, others tell a different story.

Jumbo and the other animals had finished their performances that night, and as they were being led to their box car a train came down the wrong track, possibly due to a signalling error. Jumbo was hit and mortally wounded, dying within minutes.

Thomas would most certainly have heard about this tragic event and may have held some strong opinions on its cause.

Thomas in the Canadian Census

There was a census enumerated in 1861, but Thomas does not appear in it — not in Hamilton Wentworth, nor anywhere else. It’s not unusual for individuals to have been missed, but it is unfortunate that we have no traces of him from 1851 until his marriage in 1862.

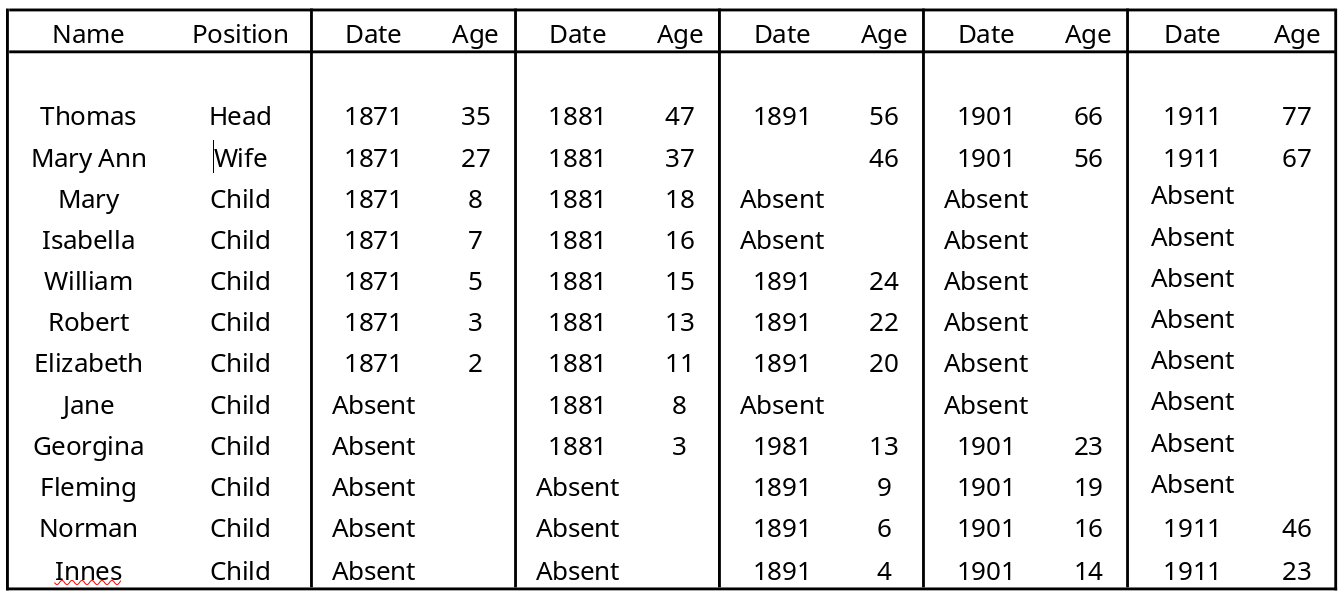

He first appears in the 1871 Hamilton census, listed as a Presbyterian with the occupation of millwright. The census records over time of his family are condensed below:

Additional information provided in those records indicates that in 1871 and 1881 he was millwright. Then, from 1891 he is listed as a Railway Agent Inspector. By 1901 he is shown as a Railway Signal Inspector. In 1911 no occupation is given.

In 1871 and 1881 he indicated that he was a Presbyterian. Then, in 1901, his religious affiliation changed to “Brethren”.

The 1911 census gives his year of immigration as 1856 and provides an address of 474 Bay Street.

Regarding his address, according to various documented sources, he lived at only two addresses in Hamilton, one being 474 Bay Street North (indicated above). The other address is only documented once, in 1884, where he is living at 239 Bay Street North.

Regarding his occupations, there is one citation in 1892 referring to him as a Foreman at C.K. Domville — a department of the Grand Truck Railway. This affiliate was involved in producing crossing frogs[6] and switches.

Another interesting piece of information is provided in the 1901 census. It gives Thomas’ annual income as $400. According to Canadian Government historical records, in 1901 annual wages (for men) across Canada ranged from $205 in fisheries to $676 for “professionals”, with $387 being typical for “miscellaneous” occupations.

This puts Thomas squarely in the middle class of his time. His immediate (male) neighbours were earning between $175.00 and $300 per annum, with only one other man nearby — a mason — earning $400/year. Various other neighbours — labourers and teamsters in this census — were averaging around $300/year. The few women who worked were earning around $150 annually,

Hamilton Events During Thomas’ Residency

Of course, much more happened during the almost 70 years that Thomas lived in Hamilton. Here is a sampling of events that may have had meaning to him, or that he likely witnessed. If we could sit down with Thomas today, I’m sure he would vividly recall these events.

1850: First street lighting using gas.

1854: Cholera epidemic with more than 600 deaths

1855: Hamilton's core has a sewer system, graded streets and planked sidewalks. Stumps, boulders, and rocks were removed from the streets, animals were banned from wandering freely on the new thoroughfares

(This marks the likely start of Thomas’ time in Hamilton)

1858: THOMAS STARTS EMPLOYMENT WITH THE RAILWAY

1859: Last public execution[7]

1860: First tap water in the city.

1860: On September 20th, the Crystal Palace opened at Victoria Park and was the area's largest fall fair for many years. The local Hamilton Herald newspaper was quoted as saying on 22 Sept 1890, "The Carnival of Venice, The Paris Exposition or the World's Fair in Chicago will be nowhere tomorrow when the great Central Fair is opened at the Crystal Palace Grounds in this city." Despite the high praise, the structure was demolished in 1891

1867: Confederation of Canada.

1868 – Hottest day then ever recorded in Hamilton at 41.4 °C.

1877: On June 20, first commercial telephone service (Fire Department) in Canada began in Hamilton, Ontario.

1877: Hamilton population hits 32,641.

1878: The first telephone exchange in the British Empire opened in Hamilton.

1879: On May 15, Hamilton was the site of the first commercial long-distance telephone line in the British Empire.

1879: The most spectacular of all fires in Hamilton was the blaze that destroyed the five-storey D. McInnis & Company merchant stores on the southwest corner of King and John Streets. The McInnes fire marked the beginning of Hamilton’s more modern fire department.

1881: First public telephones installed.

1883: Sidewalks on main streets are now paved with asphalt.

1884: The coldest temperature then ever recorded was −30.6 °C (-23.1 °F) on January 25.

1890: First bowling alley in the city opens at back of the J.W. MacDonald Tobacco shop at 66 James Street North.

1892: On June 29, the first electric streetcar was operated in Hamilton. The first two electric routes were King Street East and James Street North (right by Thomas’ home!).

1893: The Right House, Hamilton’s first large department store opens on King Street.

1893: The Sir John A. Macdonald statue arrives in Hamilton from London, England on October 30. The dedication ceremonies took place on November 1, with Prime Minister Sir. John Thompson in attendance.

1896: The Hamilton Spectator, Monday, August 25 — Thomas reports the theft of pair of oars left in a tent near north side of the bay.

1898: The first automobile driven in Canada was by textile manufacturer John Moodie, one of the founders of Canada’s first automobile club, the Hamilton Automobile Club. At its inception in 1903 there were only 18 cars in town.

1903: Thomas was in a train accident on March 18 at MARDEN, but not badly injured.

1903: Hamilton Spectator, June 1903 — Thomas complains of young men and boys hanging about the foot of Bay St, breaking doors and locks to his boathouse.

1906: Hamilton Street Railway strike takes place. Violent ensues and marks one of the few times in Hamilton’s history that the Riot Act is read and enforced.

1907: In October, Thomas goes abroad (location unknown) with his daughter Innes.

1913: Increased population and prosperity results in a building boom. As a publicity stunt and raffle, workers and contractors built a house in a day in 1913 which was later memorialized in a Ripley’s Believe It or Not cartoon.

1916: The Hamilton Spectator Thursday, Jun 22, 1916 — There is a fire at Thomas’ boathouse at the foot of Bay St, $50.00 damage.

1920: There were 6,000 cars on Hamilton streets — a ratio of one car for every 15 people, higher than that of New York, Chicago, Boston, or Toronto.

Thomas’ Children

Thomas had 12 children, several of whom married and had offspring of their own. Here is a brief timeline pertaining to these children:

Mary Renton (Hamilton 1863 – Toronto 1942)

Thomas’ first child, Mary, was born on April 11th. In 1884, she married Andrew Gibson Whyte.

Isabella Fair Renton (Hamilton 1864 – Burlington Beach 1910)

Isabelle was born on September 18th. In 1886, she married William Hawkins. Their son, William Hawkins would later marry a direct descendent of Robert Land, a famous Hamilton pioneer.

William McLeod Renton (Hamilton 1866 – 1938)

William was born on March 20 and later married Florence Elizabeth Warner.

Robert Renton (Hamilton 1868 – Toronto 1915)

Robert was born on December 26. He married May Hill in Toronto in 1902

Thomas was clearly proud of his son Robert, and shared this story with the Hamilton Spectator:

FOES CELEBRATED: Thomas Renton Tells How Xmas Was Spent in Trenches. Thomas Renton, 414 Bay street north, this city, has forwarded to the Spectator an account of how the British and Germans joined in celebrating Christmas day in the trenches, the account having been written by Mr. Renton's nephew.

Corp. Renton of the Seaforth Highlanders writes: Christmas — I never thought we would spend Christman the way we did. We were in the trenches on Christmas day. On Christmas eve, the Germans front of us started singing what appeared, to be hymns, We were shouting for encores (their trenches are only about 150 yards in front of us); kept the singing up all night.

On Christmas Day some of them started to shout to us to come across for a drink. It started with one or two going over half-way and meeting between the two lines of trenches; then it got that there was big. crowd of German and British all standing together shaking hands and wishing each other a merry Christmas. Tney were giving us cigars and cheroots [sic] in exchange for' cigarets [sic], and some of had bottles of whisky. They seemed to be a decent crowd that was in front of us.

They were all fairly well dressed and the majority of them could speak broken English. Some of them could speak it as well as myself. They said they were not going to fire for three days. They kept their word, too; there was no rifle fire for two days after Christmas. There were two dead Frenchmen between our lines. We could never get out to bury them till that day. The Germans helped us to dig the grave. One of their officers held a service over one of the graves. It was a sight worth seeing, and one not easily forgotten--both Germans and British paying respects to the French dead.

I received Meg and Aggie's parcels to-day, also one from the provost of Coldstream, I think I have eaten more this Christmas than what I would if I had been at home

It would be all right out here if not for the miserable weather. But it can't last always.".

The Hamilton Spectator reported:

Died in Toronto, from injuries from a fall (down the stairs – ed. Note) - while visiting his brother in law. ROBERT RENTON BURIED. Caretaker of Fern Avenue School, Toronto, Laid to Rest. Hamilton, Nov. 27.-The remains Robert Renton, a former wellknown [sic] resident of this city and employe [sic] of the Grand Trunk Railway, who died in Toronto, were brought to this city on Thursday afternoon for burial. Deceased was the second son of Thomas Renton, formerly signal inspector on the Grand Trunk Railway for fifty years, who is now retired.

Deceased was formerly a patternmaker for the Grand Trunk Railway Company, with whom he served his apprenticeship. He was well known around Hamilton Bay, where he was very instrumental in saving life, for which he received Royal Humane Association's certificate. He was a member of the Lodge of Strict Observance, A. F. and A.M., of this city, also past preceptor of the Black Knights of Ireland, No. 292; past master, of the Loyal Orange Lodge, 342 and 913. Toronto. Deceased moved from this city nineteen years ago, going to Toronto, where he was for ten years in the service of the Grand Trunk Railway Company and nine *years with the Board of Education. He was president of the Caretakers' Association and district of the I.0. 0. F. lodge of Toronto. The late Mr. Renton was 47 years of age. The funeral took place yesterday afternoon from the residence of his father, Thomas Renton, 474 North Bay street. R. McCory, of the Brethren, conducted the service. The pall were: James Massie.A. Robinson, and D. Robinson, of this city; and John Hall, Thomas. Ralston, and K. Stewart, of Toronto.”

Elizabeth Tindill “Lizzie” Renton (Hamilton 1869/1872 – Stoney Creek 1958)

There is some confusion on the actual year and date of Elizabeth’s birth — some records indicate August 10, another August 20. She married a man named Thomas Douglass Harrison Jr.

Thomas Renton (Hamilton 10 February 1871 – 18 February 1871)

George Renton (Hamilton 21 June 1872 – 23 March 1873)

A twin who died in infancy.

Jane Renton (Hamilton 21 june 1872 – 13 August 1883)

A twin who died in childhood.

Georgina Renton (Hamilton 1881 – Hamilton 1948)

Georgina was born on January 23, and in 1904 married George Grant Halcrow.

Fleming Fair Renton (Hamilton 1881 – Toronto After 1940)

Fleming was born on September 5, and in 1910 married Alice May MacLean. The last official documentation is a Toronto voters’ list from 1940.

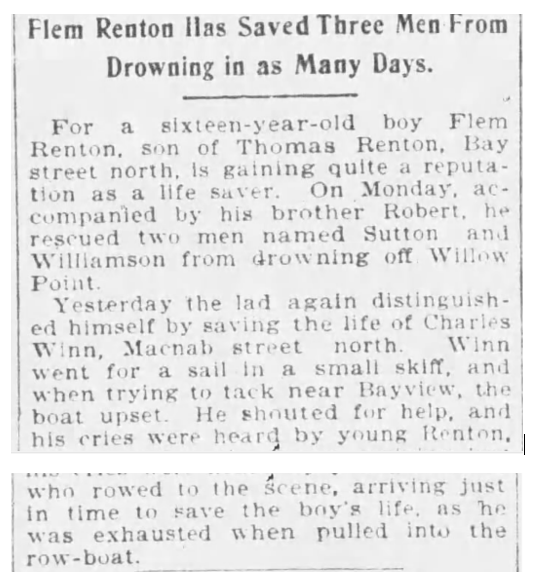

A Hamilton Spectator article on Fleming Renton reports:

Fleming has a history in Toronto as well as Hamilton. He worked at the Hughes School that used to be located on Innes Avenue, at 237 McRoberts Ave. At the time when the school was new and considered “modern” it needed a qualified caretaker to manage its steam heating and other systems. In 1917 the Daily Star wrote about what was needed for the task: “All of the appointees have engineer’s certificates and mechanical skills.” This described Fleming who was already employed as an assistant engineer at the Harrison Baths, a public pool and bathing family in the same city ward.

This was a perfect situation for Fleming who as a very young man had been a strong swimmer. On august 12, 1898 he was written up in newspapers for his remarkable and heroic rescues of three Hamilton swimmer who almost drowned had he not intervened (see article above).

Here is a quote from the Hamilton Spectator:

DESERVES RECOGNITION sixteen-year-old boy Flem [sic] Renton son of Thomas Renton Bay street north is gaining quite a reputation as a life saver On Monday accompanied by his brother Robert he rescued two men named Sutton and Williamson from drowning off Willow Point. Yesterday the lad again distinguished himself by saving the life of Charles Winn Macnab street north. Winn went for a sail in a small skiff and while trving to tack near Bayview the boat upset. He shouted for help and bls cries were heard by young Renton who rowed to the scene just in time to save the boy’s life as he was exhausted when pulled into row-boat”.

Fleming married Alice May McLean, a local Toronto girl from 64 Lansdowne Ave, on March 30th, 1910. The wedding was solemnized by Re. Bernard Bryan, the founding Rector of the Anglican Church of the Epiphany in Parkdale (Queen St. West and Beaty).

Fleming’s firstborn, Thomas, was born at Alice’s home on Lansdowne one year after their marriage. At the time, Fleming’s brother Thomas was working as the caretaker for Fern Avenue Public School in Parkdale, and he likely put Fleming in touch with the Hughes School.

Alice and Fleming moved to 189 McRoberts and stayed until 1915. They then moved to a larger home at 215 McRoberts Ave.

Norman McLeod Renton (Hamilton 1884 – Hamilton 1919)

Norman was born on November 21, and died, unmarried, on the April 26, 1919

Innes or Ennis Myrtle Renton (Hamilton 1887 – Hamilton 1919)

Innes was born on January 2, and on December 23, 1919, she married John Thomas Anderson.

The Death of Thomas — Hamilton, June 6, 1920

From the Archives of Ontario; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Registrations of Deaths, 1920; Series: 273, Thomas died of heart disease on June 6, 1920. His residence was given at 474 Bay Street North, where he had been living for either 50 or 60 years (the document is smudged, so difficult to read) and had been living in Ontario for a total of 67 years. The certificate lists his mother as “Mary Warden Fair” but this is likely inaccurate. The death was registered by his daughter, Mrs. George Haleron of 379 Bay Street North.

According to Kingston newspaper British Weekly Whig, Thomas died while sitting down to dinner with extended family — and at 6PM had a heart attack. The papers go on to say that he was G.T.R. Grand Truck Railway Employee, and had lived in Hamilton for 67 years, working 50 years at the railway. Calling him “bright and interesting” — would reminisce of early days there and “closely identified with his business, fraternal and military objectives”.

They further mention that he came to Canada at 19 years of age, had always lived in Hamilton, only living in 2 houses. Additionally, it was mentioned that 55 years prior to his death Thomas had been a gunner in Hamilton Field Battery and was the first local man to fire a shot in the Fenian raid.

They also cited that he was one of the oldest Masons in the city, becoming a member on June 25, 1875, of the “Strict Observance” lodge.

[1] 1841 Census, Parish of Westruther, Berwickshire, Enumeration Book 4, Page 6; Index, Scottish Indexes (https://www.scottishindexes.com/41transcript.aspx?houseid=75604033: accessed 21 Nov 2024); Original Source: 1841 Scotland Census, National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

[2] Janet was born on 29 July 1834. She later married a Thomas Swanson and they both emigrated to Australia in 1866 on the vessel “Prince of Wales”. Janet died at the age of 40 in September 1874 at Tiatuchia, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula, South Australia.

[3] Blainslie is a very tiny village, near Galashiels, and not far from his family home.

[4] Views of Canada and the colonists embracing the experience of an eight years' residence; views of the present state, progress, and prospects of the colony; with detailed and practical information for intending emigrants by James B. Brown. 1851. A reference well worth reading in detail.

[5] A gunner would have been one of the men who loaded a cannon prior to firing it.

[6] “A railroad frog is a device that helps the wheels rolling from one track to another. It is also called the “common crossing”. As a part of the railroad switch, it takes the area where two rails cross. Crossing nose and wing rails are main parts of the frog.” — Courtesy https://railroadrails.com/information/what-is-railroad-frog/.

[7] On June 9, 1859, John Mitchell (a.k.a. John Meehan) was hanged in a public ceremony in Hamilton. He was reported as saying, “I ask pardon of Jesus Christ for the sins of my past life,” and turned to look at the thousands of spectators who came to witness the execution performed on gallows that had been built for the occasion and painted black. Mitchell had been convicted of killing his girlfriend, Eliza Welsh, after he fell into a rage.

Here is The Hamilton Spectator’s account:

For the first time within a period of 20 years, the spectacle of a public execution was witnessed in this city today. John Mitchell, alias, Meeham, convicted of the murder of Eliza Welsh, at the last assizes of the County of Wentworth, underwent the dread penalty of death on the scaffold this morning, in presence of a large concourse of people.

At precisely seven o’clock the mournful procession of twenty moved from the gaol to the scaffold. The condemned criminal walked with a firm step and bold carriage.

When placed on the drop the very Rev. E. Gordon, V.G. said: “Do you acknowledge the justice of your sentence?” With some hesitation he answered, “I do; and I ask pardon of Jesus Christ for the sins of my past life.”

The Very Rev. Father and Father Cayan then knelt and engaged in prayer. Whilst this was being read, the executioner stepped forward and adjusted the rope around the neck of Meeham. The nervous twitching of the lips and muscular motion of the face, showed the amount of trepidation of the last awful moments of the dying man. Turning his eyes towards the sea of upturned faces which were gazing at him, he knelt on the fatal drop. All was now ready, and while the clergymen were praying, the Sheriff gave the signal.

The dead bolt was shot and the fatal drop fell at ten minutes past 7 o’clock. The neck was broken by the fall and in a very few moments all was over.

Fifteen minutes after the gaol physician having pronounced him dead, the body was cut down and prepared for interment.”