Emalyn Smith Burney: An Endling

I can’t go on. I’ll go on.

— Paul Kalanithi, When Breath Becomes Air

Emalyn first came to my attention in a sensational newspaper article from the Berlin News Records, April 26, 1913 (now Kitchener-Waterloo, Ontario, Canada):

He Died Again but Shock Killed his Grandmother

Butte, California, April 26, 1913

While mourners and relatives grouped about the open coffin of Mr. J. R. Burney’s three-year-old son Thursday, listening to the funeral service, the body moved. The child, clad in a shroud, sat up and gazed about the room. His eyes caught those of his grandmother, Mrs. L.P. Smith, 80 years of age,

The aged woman stared at the child as if hypnotized. Then she sank into a chair dead. As she fell, the child dropped back into the coffin, from which it was quickly snatched by the mother.

The physician said there was no hope for the boy and death came a few hours later. Yesterday there were two coffins in the Burney home. Double services were held and the child and its grandmother were buried side by side.

All this sounds quite sensational, but the reality, although deeply tragic, was somewhat more grounded in reality. What seemed to have happened was that the child had choked while eating a banana. Then, during the funeral services being held in the home, the grandmother, along with a pallbearer, were leaning over the boy and saw the child’s eye “relax” or twitch. At this point the grandmother fainted.

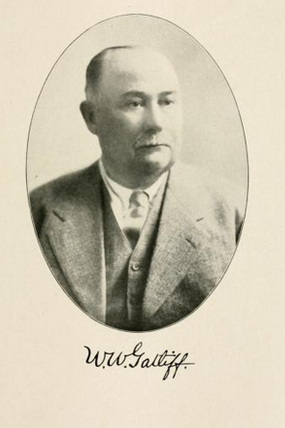

A doctor by the name of W.W. Gatliff was called in. He stated that what had been witnessed was a post-mortem relaxation of the eyelids, confirming that the child was still dead, and had been since the preceding Tuesday.

Other newspapers reported that what really happened is that the grandmother asked to hold the body of the toddler. His arm fell to the side and the grandmother thought he had returned to life.

But the grandmother did indeed die during or shortly after all the commotion.

The newspapers were a little less forthcoming with the names of those involved, and perhaps — as we shall see — with reason.

Why Emalyn? And What is an Endling?

Right now, before you read this sketch, Emalyn is less than a rumour, less than a footnote, less than a footnote to a footnote; she is utterly forgotten and unknown. Yet she once walked the streets of California. She was a woman with a story. She pushed forward in another time and place. Who knows what she might have done beyond what we will read here, what she may have become?

In the spring of 1996, the scientific journal Nature coined a new word: “endling”. The article was rather poetically entitled “The Last Word”. Created to describe the last known individual of a species (or subspecies), once an endling dies, that is the moment of extinction.

Although Emalyn is not technically an endling — our species is far from extinct — her branch on the family tree withered and died through a progression of profound tragedies. Almost everything about her has been obliterated, lost, destroyed, or discarded — as though she never existed.

Today I cannot imagine anyone other than myself and perhaps some distant reader, caring about Emalyn’s story. Yet she existed. She was a daughter, a sister, a wife, and a mother. She lived.

It is highly unlikely that there is anyone alive today who knew her. What can we call those who came before and those we can barely know? Even today, what do you call those who make up chance encounters — people who pass by on the street, in their cars, at the grocery store? Maybe those who quickly glance our way and move on? What about those people who circle our periphery, who somehow remain in our thoughts, shadows of memory yet no longer in our reach? I don’t believe we have a word for these people.

If however, this word existed, it could be applied to Emalyn. During her life, she interacted with hundreds or even thousands of people. Some encounters would have been merely a light brush, others profoundly meaningful. Yet almost all traces of her are lost; she is a relict in every sense of the word — both current and archaic. She is an endling.

What follows is a sliver of history, a recounting and gathering of what scant traces of her remain. Let us, now, try to honour her life.

Rebellion, Ruin, and Redemption

Who was Emalyn? It has taken a long time to answer that question, a siren calling through time. Writers, historians, and biographers strive to understand the heroes and the villains, but almost no one cares about those who don’t fit neatly into either category.

Author Stephen King, in his book On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, defined one winning formula as the “Three R’s—Rebellion, Ruin, and Redemption”. We all know stories that follow that path (in fact, Oprah Winfrey’s book club recommendations almost always reflect this).

Did Emalyn rebel? Did she transgress the norms of her world? Perhaps. There are hints of it in her story, and also in the path taken by her mother. Did she come to ruin? Absolutely. Did she attain redemption? We may never know.

Did I Choose the Story, or Did the Story Choose Me?

All we really “know” about Emalyn is that tragedy followed her throughout her life like a hungry wolf. We don’t know with certainty her date or place of birth; the date and place of her marriage; nor where she finally ended her days.

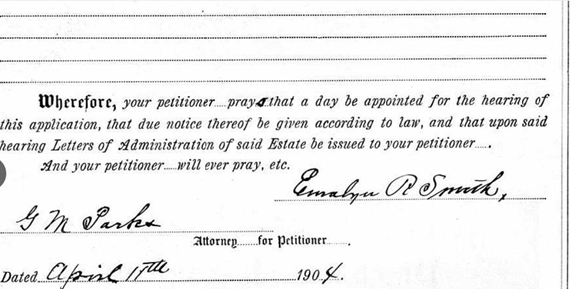

There isn’t even any certainty about her name. She is variously documented as Emalyne, Emalyn, Emmalyn, Emmalyn, Emaline, Emmaline, Emma, or Emily; and her middle initial is sometimes shown as “R”, but what it stood for is long forgotten. Her signature did however appear in probate documents, and she signed “Emalyn R”. In this narrative we will call her Emalyn, accordingly.

The chronology is sparse:

1877

- Born possibly in December 1877, in California. Some documents give Kentucky as her birthplace, but California is more likely.

- She had an older brother named John David, who was born in California on the August 17th, 1875

1903.

- Her father, Lewis Payton Smith died on December 17, 1903.

1904

- Her brother, John David died on March 29, 1904, when he was 28 years old, and she was about 25 or 26 years of age.

1905

- Married, likely in California, circa 1905, at ~28 years of age, to John Royden Burney.

1906

- Gives birth to a son, Royden “Roy” Edwin, in 1906.

1908

- Gives birth to a daughter, Annella or Annela Sue, on May 28, 1908.

1910

- Gives birth to a son, Charles Payton (or Peyton), on January 5,1910.

- Her husband John Royden Burney dies in an accident on January 9.

- Her daughter Annella dies on February 14, 1910, due to an “infantile disease”.

1913

- On April 22, the youngest son Charles Payton dies (more on the circumstances later).

- On April 23, her mother, Mary Jane Smith (née Jones) dies from shock.

1914

- Her remaining son, Royden, is raped and murdered sometime in December 1914.

1915 to ?

- She went to Quincy (California) or to Nevada, perhaps, and from there nothing further is known.

The “Original” Family

The boy with the fluttering eyelids was named Charles Payton Burney, although records variously call him Charles Peyton or Payton. He was born in Glenn County California on January 5, 1910, and died on April 23, 1913, shortly after his third birthday.

Charles Payton makes his first official appearance in the records during the census of May 3, 1910. He was four months old. His home address is given as 5A Butte City Road, Township 5.

The household comprised:

- Mr. John Burney, husband and head of household, a farmer, aged 30

- Mrs. “Emma” Burney, wife, aged 30

- Royd Burney, son, aged 4 (elsewhere called Royden or Roy E. Burney)

- Mary Smith, mother-in-law, aged 74

- John De Ber, a hired hand, aged 20 (unmarried, originally from Michigan)

In 1910, the neighbours of the Burney family were, for the most part, farmers. Most were born in California with a few exceptions (one each from Georgia, Finland, Kentucky, Indiana, Connecticut, New York, Texas, Illinois, Oregon; two each from England, Ireland, and Nebraska).

Other than farmers, there is a Justice of the Peace (William Henry Gardner, age 49, b. 1861), a schoolteacher (Josie Kendrick, 32 years old, b. 1898, unmarried) and a divorced laundress (Nelly W. Hughes, age 32, b.1898) supporting 4 children (2 boys and 2 girls).

John Royden Burney

John Royden Burney was born likely in March, in California, between 1872 and 1874, and died June 9, 1913, less than two months after the death of his youngest son. John was buried in Afton Butte, California in the Marvin Chapel Cemetery.

He was a farmer and a registered Republican voter in Butte, California.

There is not much history about John Royden. He makes an appearance in the 1900 California census of 1900, where he provides his age as 18. He is a day labourer and indicates that his father was born in Arkansas (or possibly in Maine) and his mother in California. John said he could read, write and was renting a place to live in Sierra. He lived alone. We will come back to John Royden later.

The Beginnings of Tragedy

Where is the beginning of anything? Is the end of one thing the start of another?

Emalyn’s family origins can be traced to Kentucky; Lawrence County, Illinois; Butler County, Ohio; Crawford County, Illinois; New Jersey; and Wales. The men and women who came together over a period of time (reliably) beginning in the mid-1700s were prolific and daring, as many were in those times and places.

Four Generations Before Emalyn

There are many bits and pieces of speculative genealogy available that trace the families associated with the ancestors of Emalyn, but the most credible trail starts with a Welshman named Moses Jones.

Supposedly, Moses left Wales sometime in the mid-1700s to come to the New World. Or not. It is more likely his son, Aaron, made the perilous journey to start life anew, far from home.

Three Generations Before Emalyn

Aaron Jones may have been born somewhere in Wales on August 16, 1774 or 1776. He married a twenty-year-old girl, Mary Shepherd (from New Jersey) in 1798, possibly while in Virginia.

According to a newspaper article from the Palestine Registry dated February 15, 1962, which was entitled “Frontier Hardships Plagued Early Settlers”, Aaron’s grandson, William recounted that the former was one of the first settlers of Flat Rock, Illinois. It is William who provided the connection to Wales, stating that “he” came to Virginia with his family. (It is unclear whether the “family” he referred to is that of Aaron’s parents and siblings, or that of his wife, but, according to some sources, Aaron came with his father Moses prior to the Revolutionary War). Around 1798, he and his family went to Clough in southern Pennsylvania, and from there to Oxford, Ohio in 1831. He then, along with several unnamed family members went to Crawford County, Illinois and acquired land around the area which would later become Flat Rock village.

As is often the case, dates, and places become blurry over time and in the census of 1880, Aaron’s son Hiram claimed that both his parents were born in Virginia.

In any case, Aaron was a soldier in the War of 1812, fighting in an Indiana infantry regiment.

Not much is known about Mary Shepherd, other than she was of “Scottish” descent.

Aaron and Mary had at least seven children, all living quite lengthy lives and having many children. At this point the family appears relatively prosperous.

Aaron died in Illinois on January 29, 1847, and his wife in December of the same year. Both were buried in the Jones’ family cemetery in Flat Rock, Crawford County, Illinois.

Two Generations Before Emalyn

Aaron’s son Isaac was born in Oxford, Butler County, Ohio on July 24, 1804. And here things become confusing. According to some sources, he married a woman named Mary Badgley (or Badgeley) on April 10, 1834, in St. Clair, Illinois. Mary herself was born on December 12, 1809 (and later died on December 31, 1841, in Crawford County.

But that doesn’t work. Mary could not have been born before her son. There is another hint of a marriage in the records — this time to a Mary Purcel in Ohio on June 17. 1830. This Mary Purcel was supposedly born in 1794 and died in February 1834. According to letters exchanged by various descendants, Mary Purcel had four children, all of whom died in childbirth or shortly thereafter.

There is considerable overlap in the dates, so it is difficult to untangle who were his wives, and who were mothers of which of Isaac’s children. Further confusion emanates from references to another mysterious wife named Jane Arpas. What is clear is that Isaac later married a woman named Charlotte Reavill with whom he had several children.

In any case, Aaron appears to have been upwardly mobile. In 1840, he is living in Crawford, Illinois. By 1860, he was a farmer living in Bond, Lawrence, Illinois and holds $4560 in real estate and another $1000 in various assets. By 1870, his real estate is valued at $5500 and personal assets at $2000.

Isaac and his wife (or wives) had several children:

- Mary Jane (1835-1913) — Emalyn’s mother and the daughter of Mary Badgeley.

- Elizabeth (1837-1840)

- Abner (1838-1916)

- Rachel (1838-1840) — Possibly an erroneous birthdate; also, could Emalyn’s middle initial come from this source?

- Julia Ann (1840-1845)

- Lewis Travis (1843-1930)

- William (1845-1845, died in infancy)

- John D. (1845/1847-1899)

- Adeline or Cydaline (1849-1877)

- Nancy Ann (1851-1875)

- Harriet Isabelle (1854-1855)

- Emeline or Emma (1855-1889) — Here begins a more definitive note of tragedy. The young woman died from drowning or from a protracted illness. Perhaps our Emalyn was named for this aunt.

- Isaac Junior (1858-1939)

- Rose (Rosey or Rosa) Ann (Annie) (1861)

And here, in this family, we begin to see the tendrils of sorrow start to grow. Wives dying, their children dying young, drownings.

Isaac’s third wife, Charlotte, died on Oct 26, 1870. She had been digging up potatoes with some kind of hoe, cut her toe and it became infected. She underwent two separate amputations, but to no avail. Mary Jane, Emalyn’s mother, certainly knew her stepmother and some, if not all of her step-siblings, but Charlotte’s death may have occurred after Mary Jane had already left for California.

Rose, Isaac’s youngest child, went to California to stay with her step-sister, Mary Jane, for a couple of years, but she returned to Illinois to care for her other sister, Emma until the latter died in 1889. Rose later married and moved to Kansas.

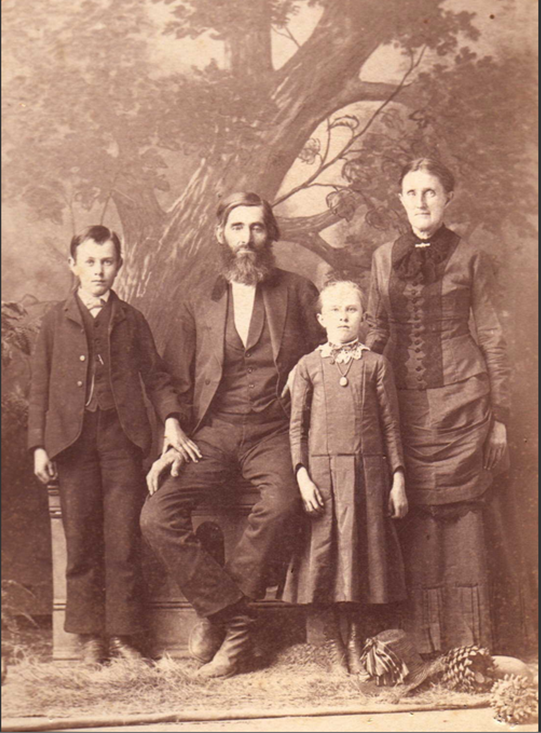

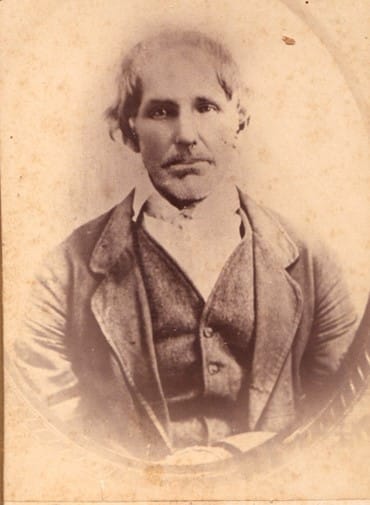

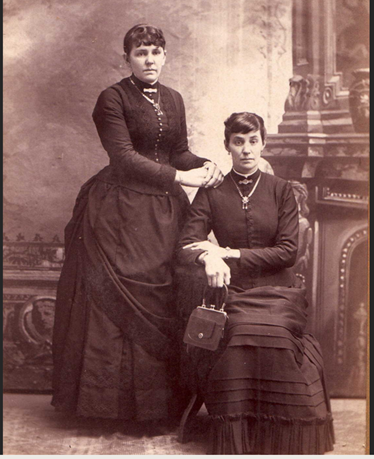

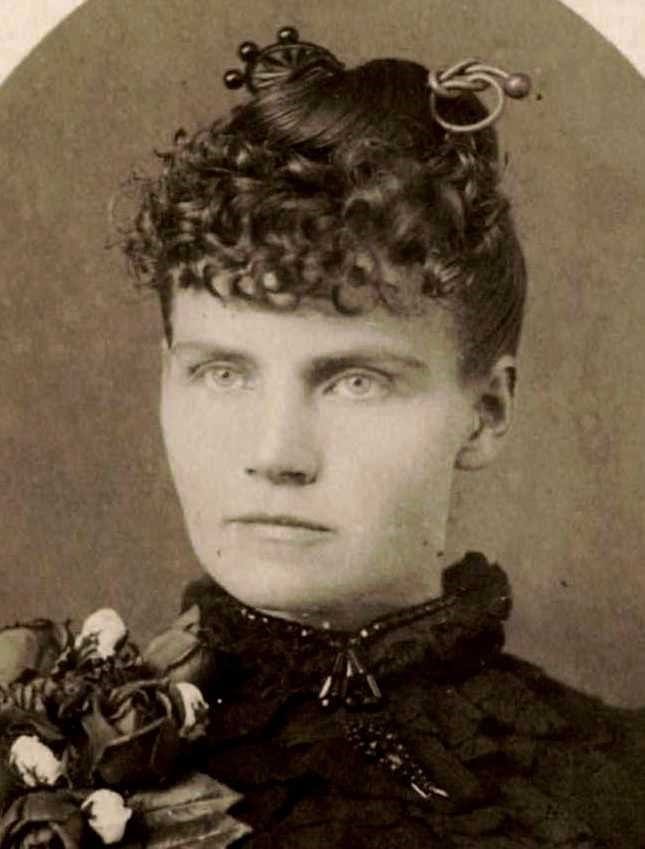

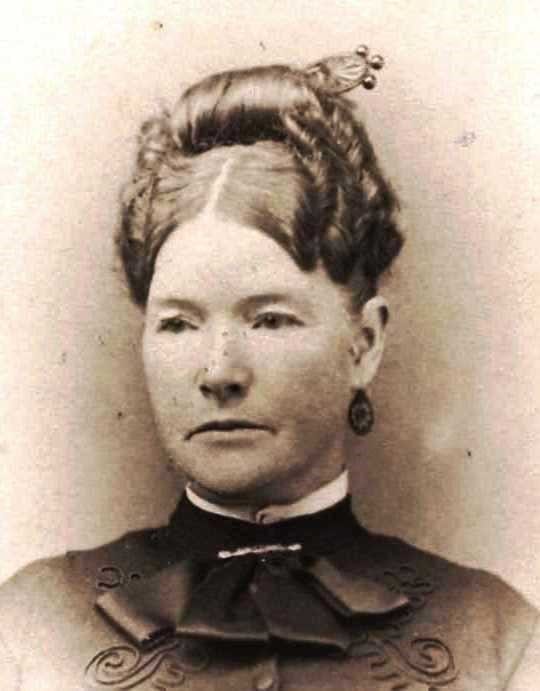

I found another photograph of Emalyn's mother, Mary Jane, in a photo album from Kansas during research for this article:

Looking at the original family portrait of Emalyn’s mother, note the dress. Mary Jane is wearing the same dress in both pictures. Note the brooch — it too is the same.

The picture (above) with the unidentified sister shows the brooch yet again. Could this clearer and younger photograph show Mary Jane before her trek to California? If so, how dramatically she aged. But this may not be Mary Jane, as Rose Ann doesn't look that much older.

In any case, the two pictures of Rose and Mary Jane were clearly taken about the same time, while Rose was in California.

There were no photography studios in Glenn County at the time, only itinerant photographers passing through. One would imagine that when one passed through town, Rose and Mary Jane decided to have the pictures taken so they could be shown to the family back East. And the only reason we have any pictures of Mary Jane and Emalyn is because Rose brought those pictures back with her, took them with her to Kansas, and her family saved them for decades.

Thank you Rose.

Over the years, Rose’s family and other descendants of Isaac Jones knew very little about Mary Jane and Emalyn. A family letter mentioned that:

Mary [Jane] married Peter [sic] Smith who died on a ranch near Butte City, leaving one son over twenty who died shortly [after] and a daughter Emma [sic], of whom I could learn little, moved away

And with that tiny paragraph, Mary Jane and Emalyn disappeared from their family back east.

One Generation Before Emalyn

Emelyn's mother Mary Jane Smith (née Jones) was born in Lawrence County, Illinois on December 23, 1835. By 1856, she had married Lewis Payton (or Peyton) Smith in the same county. Or at least it’s probable they married.

The records in Lawrence County list Mary Jane and Lewis Smith as having applied for a marriage license in 1856, but that it was “not used”. After scanning several pages of marriage licences in that county and in that time period, there is no other couple where the words “not used” appear. What this means is unclear. Did they not marry, did they marry elsewhere? Did Mary Jane run off to California with Lewis? Perhaps Lewis went off to California first and then had her join him?

And here lies one hint of rebellion or transgression. Or maybe it's nothing at all.

By 1880, the couple are in Butte County, California. Sadly, we have no photographs (other than those above), showing Mary Jane or her family and friends, but we do have the names of her 1880 neighbours — the women who were close to her in age: Margaret Smith (31), Catherine Kerrick (38), Sarah Morse (50), Ella Pate (26), Harriet Butler (35), and Lucinda Grinstead (43).

One wonders if Mary Jane was friends with these women. Did they get together for sewing, swapping recipes, trading stories, offering advice and consolation? Did they recall their families who might have been far away? Did they talk of dreams and ambitions, or was the conversation more work-a-day — the weather, the health of the animals, child-rearing, and planting lore?

Returning to focus on Mary Jane, once again, the details are lacking. She and her husband, Lewis Payton, may have had a son named David. This David may have been born after 1856 and died prior to 1875.

In any case, the first documented child of the couple was John David, born in Butte County, California on August 17, 1875. John David is listed in the California Voter Records from 1880, where he is described as a labourer. He is 5’ 9” tall, with a fair complexion, blue eyes and dark born hair. John David never married.

What ultimately happened to John David is unclear. He was supposedly incarcerated in the Allegheny (Pennsylvania) County Workhouse on December 1, 1900 (prisoner no. 94811), where his crime is that of being a “suspicious person”.

Not long after this, on March 29, 1904, Emalyn’s brother, John David died.

Emalyn’s Father: Lewis Peyton Smith

The documentation is still sparse on the origins of Emalyn’s father, but what seems reliable is that he was born on August 10, 1827, somewhere in Kentucky and that his parents were from the same state.

On August 10, 1839, a Lewis P. Smith is granted 40 acres land in Lawrence County, Illinois, along with Serena Smith and Harvey Smith. Harvey appears again; there is a mention in the Lawrence Illinois census of 1850 of a Lewis P. Smith, born in Kentucky, age 46 (but this is likely a date error), who is farming land in Bond, Illinois. He is there along with Helen Miller (age 23) and Harvey Smith (age 19), both also born in Kentucky.

On the July 1, 1851, we find Lewis P. Smith again being granted the same piece of land from 1839, but now no longer including others on the deed.

How Lewis came to Lawrence Illinois is unknown, but it was there that he married Mary Jane Jones in 1856. Lewis’ parents are unknown and there is no information on whether he had any siblings. As mentioned above, another unusual fact is that the Illinois State Marriage Office does record Lewis and Mary Jane as having a marriage license, but (again) it was denoted as “not used”.

Lewis comes to life in the records after his marriage. In the Federal Census of 1860, we find him living and farming his own land in Bond, Lawrence County, Illinois along with his wife Mary. The census gives his first name as “Paten” or “Paton”.

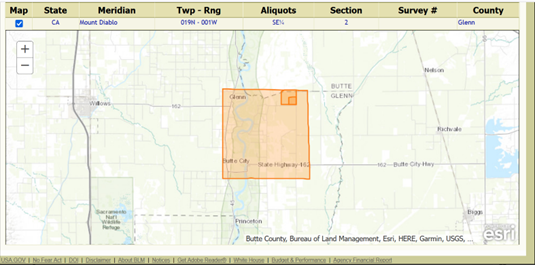

In 1874, on March 20, the Marysville Land Office gives Lewis 160 acres in the Mount Diablo section of Plumas County, California (accession no. AGS-0355-430 in the Land Office Registry as surveyed on July 2, 1862).

What is of note is that some of the documentation refers to land given to Lewis by Ulysses S. Grant. This is certainly of interest because it suggests that Lewis fought on the side of the Union during the Civil War, and also provides some validity to his having been married in Illinois in 1856.

If he was indeed born in 1827, he would have been of soldiering age in the 1860s. Kentucky was initially neutral during the Civil War, but then things became exceedingly complicated as one might expect — it was the birthplace of both presidents Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis. In any case, the State and its population was split, with somewhere between 25-40,000 Kentuckians serving as Confederate soldiers and 74-125,000 as soldiers for the Union.

It is likely that Lewis was on the Union side, but one wonders if the lack of family information might stem from some deep divide in political sympathies. We may never know.

In any case, the 160 acres in that particular area of California was almost certainly granted pursuant to the 1862 Homestead Act. This Act gave precisely 160 acres of public land to a head of household in exchange for a small filing fee ($1.25/acre) and a promise of residence of five years during which time very modest improvements were to be made. If Lewis had been a Union Soldier, he could have deducted time served from the five-year required residency. In any case, many of the potential “farmers” who were granted land did not have the financial wherewithal to purchase the tools needed to farm, livestock, seeds, let alone to build decent habitations. There was, of course, some abuse of the system, and many homesteaders became miners and loggers (not to mention speculators, cattlemen, and railroad owner/operators).

Based on Lewis’ obituary, it seems possible that he may not have farmed the land he was granted. According to the Chico Weekly Enterprise, Lewis came to California at the “height of gold fever” and crossed the plains in 1850 by ox teams. Perhaps the news article was a little off in dating the time Lewis actually came to California, since he was still in Illinois in 1856 and was only given land in 1874. Unless, of course, he came previously, returned to Illinois and then back again to California.

Regardless of the dates, the Chico paper recounted how Lewis had been mining in different parts of the Sierras, going as far south as Amador County. After his time mining, he came to Butte County and began farming.

Mount Diablo: A Place of Many Names

Prior to his ‘settling’ down, it is likely that he was active in some fashion in the Mount Diablo area, which had other names prior to the Spanish moniker:

Tuyshtak, meaning “at the dawn of time”;

Sukkú Jaman, a Nisenan name meaning “dog mountain”; according to tribal elders, it refers to a place where “dogs came from in trade”;

Supemenenu is a southern Sierra Miwok name;

Oj·ompil·e is the northern Sierra Miwok name.

The Spanish also had other names for the place:

Cerro Alto de los Bolbones or Volvones (the Spanish called the local people ‘Volvon’);

Contra Costa (a name created in 1850).

And, of course,

Monte del Diablo, meaning “thicket of the devil” (monte meant thicket, but was later mistranslated as mountain).

A Place of Sacred Origin…

Sacred to various California native peoples, both the Miwok and Ohlone believed this place to be the point of creation of the world. Their stories are believed to be over 4000 years old. One story begins when the Mount Diablo and Mount Tamalpais (Reed’s Peak) were both surrounded by water. Coyote, the Creator, and his assistant, Eagle-Man made human beings there. Another story tells of Molok the Condon, who brought forth from the mountain his grandson, Wek-Wek, the Falcon Hero.

At least 25 tribal groups knew of or lived around the mountain, and three distinct languages were spoken. Most of the area was home to the early Volvon (sometimes spelled Wolwon, Bolbon, or Bolgon) who spoke Miwok.

Not unlike the Biblical story of the deluge, the Miwok believed there had been a huge flood and the first people of the world were forced onto Mount Diablo to save themselves. When the water receded, they walked down into the valley in search of food, but found only mud, sank into it and died.

Then ravens landed on top of each spot where a person had sunk into the mud and changed themselves into the Miwok, the People of the New World.

According to the Ohlone, the old world was also destroyed in an epic flood. Coyote then stood on top of the mountain, along with Hummingbird and Eagle (some versions say it was Hawk) and offered to teach the remaining humans how to survive. Another version tells that Eagle found a beautiful woman and flew her to the mountain top to mate with Coyote. She then bore the original Ohlone people.

… Becomes a Place of Evil…

In 1805, the Spanish became aware of the mystical power of the place when, according to their stories, some Native captives escaped custody and vanished into thin air in a thicket on the top of the mountain.

It was first mapped in 1824, and found its way onto official documents in 1827.

The now familiar name is also believed to have been assigned by none other than General Mariano Vallejo (Emalyn will have a future connection of Vallejo, but more on that later), a leader during the transition of California from Mexican to American land. He officially reported the name and location of the land to the California Legislature in April 1850. People had already begun associating the place with the devil. It was said it emanated odours of sulphur, satanic bears lived there, the gold was poisonous, and there could be found huge cave-like openings that spouted the flames of Hell.

In Vallejo’s report we find the earliest “official” version of the eeriness of the place. He told of a 1806 military expedition from San Francisco that intended to subdue the Bolbones. The native people met the Spaniards at the mouth of a hollow in the western side of the mountain.

The Natives were about to win the battle. Then:

“[A]n unknown personage, decorated with the most extraordinary plumage waving his arms as if to cast a spell on the intruders” appeared on the battlefield. The soldiers departed in terror and the “unknown personage” went away towards the mountain.

The Spaniards later learned that the entity was called ‘Puy’ and that it went through this unusual and terrifying ‘ceremony’ every day at all different times. The Spaniards believed that ‘puy’ was the native word for ‘devil’.

Should we consider that this sounds like an interesting way to justify a military loss?

Another story tells of a friar wanting to suppress evidence of gold in the area or to prevent the native peoples from keeping it. The friar mixed the gold with poison and fed it to some dogs who then died in agony. He then preached to the Natives about the evil of gold so they would not touch it (seems rather convenient and contrived).

Still the stories persisted. Soldiers told of chasing horse thieves onto the area where they vanished into flaming openings in the mountain.

Even in the 20th century, campers tell of physical phenomena which could possibly lend credence to the earlier tales. A camper in 1910 told of an eerie roar coming from all around but which he believed was due to warm air rushing up the mountain sides. Another camper saw a wraith at sunrise but chalked it up to the sunlight coming through a fog.

One wonders if Lewis Payton, Mary Jane and their two children knew these stories. Did Emalyn and John David whisper them at night?

Union and Butte, Colusa County, California

Come 1880, Lewis appears in the California Voter Census and is living in Union and Butte, Colusa, California. The census provides this little tidbit of personal information: It says he is a farmer, just under 6’ tall, with a dark complexion, grey eyes and grey hair.

In the Federal Census of the same year, he appears in the same location, still as a farmer, along with his wife Mary and children. His eldest is listed as John D. (David), age five, and his youngest is “Emily”, age three. Also living with them is a 28-year-old labourer named John Johnson, whose father is Canadian and mother a Californian.

Although their level of prosperity or struggle cannot be ascertained from the census, we can find some information on their neighbours:

In general, the immediate neighbours were farmers, and mostly quite young. Other than California natives, there are six people from Iowa, five from Kentucky, three from Missouri, three from Ireland, three from Canada, two from Ohio and one each from New York and from Wisconsin.

The neighbourhood women closest in age to Mary Jane were: Elicia Kendrick (age 30), Lizzie Owen (age 35), Kate Mehling (age 20), Elsie Edmunds (age 22), Alice Young (age 36) and Margaret Crouch (age 33).

Of the more notable neighbours, we find three Chinese men — a 40-year-old cook named Sing, a 30-year-old named Chong, and a 25-year-old named Frank (the latter two being labourers).

Returning to Lewis, evidence confirms he was a grain farmer for most of his remaining years in Butte.

The Missing Time (1881-1890): The Family Portrait

Tragically, almost all the records for California, including the 1890 census records, were destroyed during a fire in the 1920s. These records would have been key in determining more about Emalyn’s story, but there is likely no hope of discovering anything more about this period in her life.

The family portrait shown at the beginning of this essay is likely the only thing extant from this period of time.

To revisit the family portrait, the children’s ages are the easiest to guess. John David appears to be around nine years old and Emalyn around six years of age. This would place the portrait as having been taken in 1883.

If the family sat for the portrait in 1883, Lewis Payton would have been 57 years of age, and his wife Mary Jane, 49. If you look at Mary Jane’s neck, she looks rather “weathered” for a woman in her late forties. Lewis Payton however does not look eight years older than his wife. Perhaps time was kinder to him physiologically. In any case, in 1896 he is described in a voter’s list as being just under 6’ tall, with grey eyes and hair and a dark complexion.

The eldest son, John David, seems to have a resemblance to both parents, despite what appears to be a widow’s peak in his hairline (but this may merely be how he combed his hair). Both father and son appear close, with John David’s hand holding his father’s, and they both appear dark-haired and dark-eyed. In 1896, John David is included in the Butte County voters list, and he is described as being 5' 8 (1.73 m) tall, with a fair complexion, blue eyes and dark brown hair.

Mary Jane also has dark hair and possibly dark eyes. She appears somewhat tense, but perhaps this is just awkwardness at being photographed. She is likely rather tall, given that she is only slightly shorter than her 6’ (1.83 m) tall husband.

Presumably they are dressed in their “Sunday best”, and if that is the case, there appears to be a hint of shabbiness to their clothing. Both the children’s outfits look a little too small for them.

Which brings us to Emalyn. She is clearly the focal point of the portrait, although the intent was more likely to have showcased the Paterfamilias. Lewis Payton has no adornment whatsoever. Mary Jane sports a tiny brooch at her neck. John David has what appears to be the chain of a pocket watch. Yet, Emalyn stands out. She is wearing a fancy collar and has a large pendant handing from her neck. She stands slightly in front of the family, looking clearly at the camera she appears resolute, confident and almost defiant. Her hair is lighter than that of the others and may have been red (more on why this might be later in the essay).

She appears to have had a forceful presence, and this side of her nature will become more apparent once her father dies. But at this young age, Emalyn had no clue of the level of tragedy she will face in the coming years.

The Death of Emalyn’s Father (1903)

Just a week prior to Christmas, Lewis Payton Smith died on December 17, 1903, at the age of 76. According to the Chico Weekly Enterprise, he succumbed to pneumonia at his home six miles west of Butte City. Emalyn is about 24 or 25 years old, and her mother is 68. A doctor by the name of William Walker Gatliff attended the final moments; we will run across him again after another few years.

Lewis is the first of the family to be buried at Marvin Chapel Cemetery in Afton, Glenn County. The cemetery is associated with the Methodist Episcopal faith and is the first and only indication of the family’s religious affiliations.

Just a week before his death, the family had made a few unusual purchases from the local grocer. They bought spices: cinnamon, mace and nutmeg, along with raisins and some sort of cooking pan. They also bought a larger than usual quantity of ham. Poignantly, it would seem that a Christmas dinner was being prepared.

On the day of Lewis Payton’s death, someone went to the local store and purchased hairpins, ribbons, veiling and crêpe, perhaps to prepare for a funeral rather than for a Christmas celebration. Aside from some coffee, tea, oil and tanglefoot (an insect repellent), there is no record of any further purchases being made.

And here begins what might be a series of surprises for Emalyn, or perhaps the arrival of the inevitable.

A Year of Reckoning (1904)

Things clearly had not been going well for the family, but whether Emalyn knew this cannot be determined. But her mother, Mary Jane, likely knew for reasons that will become clear.

The family was in financial trouble.

One month after Lewis Payton’s death, on January 14, 1904, Emalyn’s brother John David is appointed executor of his father’s estate. By the end of March he too is dead.

Despite Mary Jane being alive, on May 11, 1904, the young Emalyn is appointed Executrix and accordingly put down $500 as surety. It is on this paperwork where we can first see her signature and know that she refers to herself (at least officially) as “Emalyn R. Smith”.

Emalyn declared that the combined value of the household furniture and farm implements is $235. Real estate, meaning “improved” land of either 3.2 or 3.7 acres (the document is smudged here) was valued at $8400. Although the 160 acres on Mount Diablo would likely have been of lesser value than land in Butte, this is a marked come down.

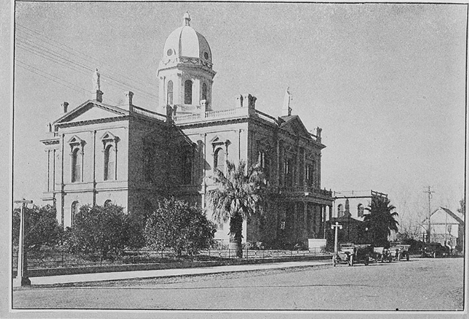

At 10am on Monday, April 25, we can place Emalyn in the courthouse of the town of Willows (the county seat) for her hearing. We know exactly where she was standing at that moment.

Her father, Lewis Payton owed a lot of money.

Starting with the smaller amounts, the family owned $32 to the aforementioned Dr. Gatliff (house calls at $8/each, and prescription drugs provided in July, November, and December).

Then we find the owner of the general store, Frank Miller, who is owed $184 (note, alarmingly, this number is just slightly less than the value of all Lewis Payton’s household goods and farm equipment).

Moving on to the larger debts, the 1900 Federal Census that listed Lewis Payton, wife Mary Jane, and children John David and “Emma R” lived at a farm that was mortgaged.

The local Willows bank was paid $5214 from the estate. This was in payment for the following:

- A loan taken out by Lewis Payton and his wife Mary Jane in May or August 1900 for $4125 at 8% interest that was supposed to have been paid in 12 months (and wasn’t).

- Later that year, Lewis Payton and his wife borrowed another $114 at 12%.

- In June 1903 (now without his wife co-signing) another loan of $175 is granted, this time at 10% interest and the entirety is to be paid in one year and in gold.

- The next month, July 1903, another loan is arranged for $60 at 12% interest.

By the time summer rolls around, in August, Emalyn petitioned the court to sell 220 sacks of barley weighing 2134 lbs., along with 350 sacks of wheat weighing 4610 lbs. She requested to be allowed to sell the produce privately and prior to the estate being settled, as the barley and wheat were perishable and would diminish in value the longer she waited.

According to historic commodity selling prices, on average in the United States in 1909, wheat was selling for about $1/bushel/60 lbs. Barley, specifically in California in 1904 was fetching $0.60/bushel/48 lbs. This means that, at best, Emalyn had $77 worth of wheat and $27 worth of barley for a total of a little more than $100.

The numbers did not look encouraging.

The Creditors (1903-1904)

Dr. William Walker Gatliff

In addition to the bank, Emalyn and her mother owned money to Dr. William Walker Gatliff.

William Walker was born in Missouri in 1857. His Kentuckian father, Elias, died in the Civil War fighting on the side of the Confederacy in 1863. William grew up with his mother. Rachel (also from Kentucky). At the age of 12, he and his mother migrated to Hood Texas where he studied medicine. He later he received his degree in St. Louis. He began his medical practice in the State of Washington, and came to Butte County California in 1887.

Initially riding by horseback day and night to attend to his patients, he later established a drug store and, by 1918, he owned a 320-acre stock ranch in the area.

Emalyn likely would have known the young Loraine Gatliff. As Emalyn’s tale unfolds, we will see that her interactions with William Walker will, sadly, continue.

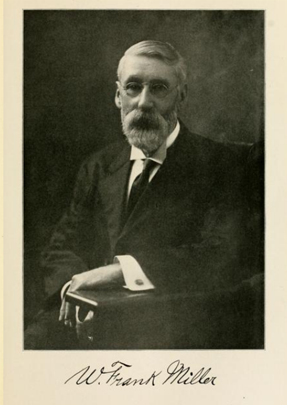

William “Frank” Miller, General Merchant

Frank Miller was owed quite a lot of money from Emalyn and her mother.

William Franklin Miller was born in Kentucky in1848. His parents, Marshall and Amanda crossed the plains in 1849 in a time of excitement of the Gold Rush, and they bought the infant Frank with them. His mother, Amanda Walker, died in California sometime around 1850, where she and her husband operated a ferry between Fremont and Vernon.

His parents, Marshall and Amanda (or perhaps of the second wife Eleanor) also had a daughter named Amanda K. Miller who was born in 1853. Tragically, in July 1855, while attending the funeral of a neighbour, the parents learned that seven-year-old Frank had accidentally shot and killed his little sister in Nevada City, California.

In July 1859, Frank’s father Marshall dies in a small settlement called Coyoteville.

Young Frank, now around twelve or thirteen years old, is on his own and begins working in the mines for around 18 months. He tries out different types of work, along with his elder brother until 1863, when they settled in Butte County. Ranching for a while, they sold their land in 1873 and opened a general store.

And this is the place where Lewis, Mary, John and Emalyn did their shopping.

Income and Expenses

Before we get into the debt owed to the local general merchant, let’s explore a few “typical” numbers from the early 1900s in California.

According to US Government records, the average family of four in California in 1903 would have spent around $340/year in food alone.

Here are some typical wages in California at that time:

- Blacksmith $2.25

- Baker $2.75

- Railway Conductor $3.75

- Stair Builder $4.00

- Brick Layer $5.00

- Labourer $1.75-2.50

In 1900, the average annual wages were:

- Surgeon $1625.00

- Banker $1600.00

- Saloon Keeper $1500.00

- Hotel Keeper $1250.00

- Lawyer $1200.00

- Journalist $950.00

- Photographer $700.00

- Waiter $500.00

- Bartender $425.00

- Servant $144.00 plus board

For perspective, in 1900 a shave would have cost 10 cents, a haircut 25 cents, and a shampoo 15 cents.

Common grocery items in 1900 include:

- Salt hog (bacon) 13 cents per pound

- Butter 25 cents

- Tea 50 cents

- Coffee 23 cents

- Sugar 6 cents

- Flour 2 cents

- Rice 8 cents

- Potato 88 cents per bushel

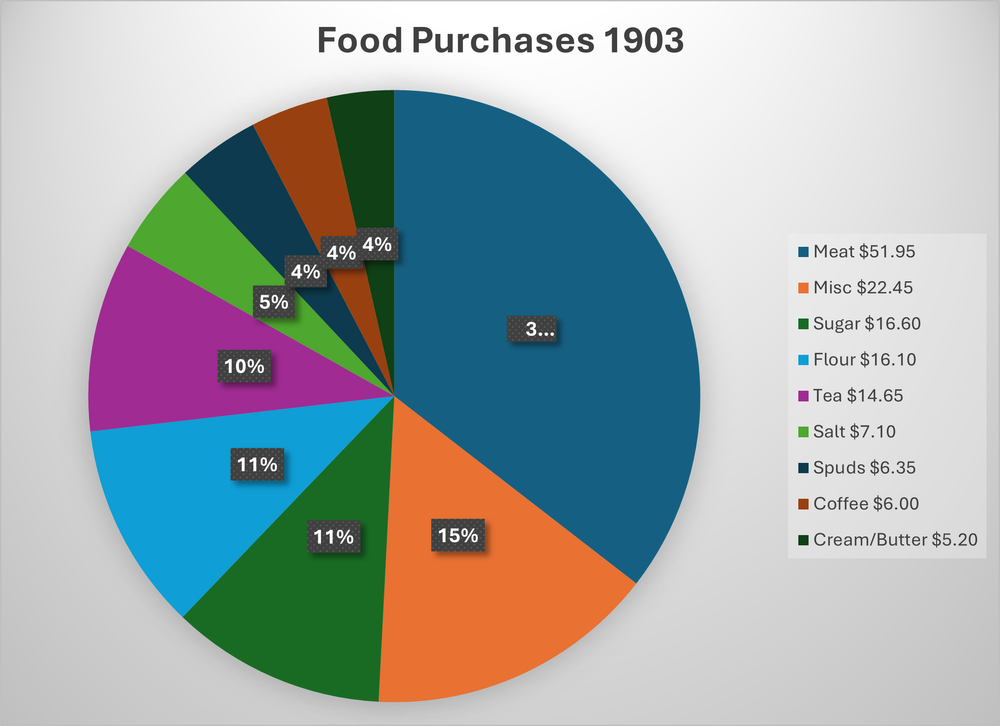

Based on the claim against the estate, in 1903 Emalyn’s family spent the following amounts:

- $130.30 on food items

- $29.30 on tools and hardware

- $27.80 on clothing (some fabric [organdy] and ready-made shoes, socks, undergarments, collars)

- $17.40 on cooking and cleaning items (pots, pans, jars, brooms, lye, soap)

What is notable is what they did not purchase. There is no tobacco, no alcohol (except for a single purchase), no milk, no eggs, no cheese, no fruit and no vegetables. The only type of meat they purchased was ham and bacon. No chicken, no beef, no fish.

Since the majority of their purchases appear to have been made at the (only) local store, we can deduce that the family grew and preserved their own fruits and vegetables (further confirmation of this is that larger amounts of sugar, salt, and vinegar were bought in the early fall); they probably milked their own cows (although didn’t seem to churn butter or make cheese); kept chickens for eggs and meat; and maybe fished on their own in nearby streams.

The pie chart below provides some insight on where the money was spent on food:

A poignant note on the subject of food: Shortly before Lewis Smith dies, someone made some unusual purchases: raisins, mace, nutmeg, and cinnamon. It would seem that a Christmas cake was being prepared.

Then, on the day of Emalyn’s father’s death, the family purchased ribbons, veiling, and crêpe: these were likely items to be used for mourning.

Emalyn and John Burney Marry (ca. 1905): A Few Good Years

There is no record of Emalyn’s marriage to John Burney, and we have no idea whether they had known each other for some time or not.

Emalyn was about 28 years old in 1905 when, presumably, she married John. This is rather unusual in itself, as in that time and place, most women would have been married already. Did she marry for financial reasons? Had her father previously opposed the match? Was she pregnant? We will never know.

Of note is that as of April 1904 Emalyn was still signing as “Smith”.

Sometime in 1906, less than two years after her father’s death, Emalyn gave birth to her first child, a boy they named (Edwin) Royden “Roy” or “Royd”. There is no birth record. In order to more closely pinpoint the date of his birth, referencing his admission to the orphanage (more on this later), Royd was seven years and eight months old between October and December 1913, putting his birth between February and April 1906, with his conception around the late spring or early summer of 1905. This is a year after Emalyn is trying to sell off her father’s wheat and barley crop.

Next, on May 28, 1908, a daughter is born: Annela (or Annella) Sue Burney.

Things Start Going Wrong (1910): Another Death

On January 5, 1910, another son is born: Charles Payton (sometimes spelled Peyton) Burney. It would seem that things are going well. But not for long.

On February 14, 1910, little Annella Sue dies of an “infantile disease”.

In the 1910 census enumerated on May 3, only the two male children remain in the household with their parents and the grandmother Mary Jane Smith. John is renting a farm on Butte City Road and has a hired man named John De Ber (a Michigan native) living there.

The census data is a little muddled, indicating that both John and Emalyn (called Emma here) are 30 years old, born in 1880. It lists John’s father as having been born in Maine — which is incorrect — but this did provide a clue as to John’s original family. His stepfather was in fact from Maine.

Things Start Getting Much Worse (1913)

And here we come to the sensational newspaper article at the beginning of this history. Young Charles Payton (variously referred to as Charles, Payton, or Peyton), on April 22, 1913, chokes on a banana and dies.

What happened afterwards was likely this: A pallbearer, Mack Staten, according to the local newspaper (this was likely a young boy named Max Staton, born in 1900 in Glenn County and living in Butte City) was among those moving the deceased young boy from the house to convey him to the burial site in Marvin Chapel, Afton. The grandmother, Mary Jane, asked to see the child one last time, and when she looked over the body, either the eyelid fluttered or more likely the child’s arm was slightly jostled and fell off his chest.

Chaos ensued. The Staton boy was startled, but the grandmother Mary Jane began screaming and crying out that the boy was not dead, that he had returned to life. Everyone is upset and Dr. Gatliff was called to the home. The doctor confirmed that the boy was still dead, and had been deceased for a few days. If it was an eye movement or an arm moving, either was probably caused by the body being moved combined with rigor mortis no longer playing a factor (after a certain amount of time, rigor mortis disappears, and the limbs become more supple).

Some accounts mention that the grandmother had been “ailing” for “some time”, but what is certain is that the shock put her over the edge and she died.

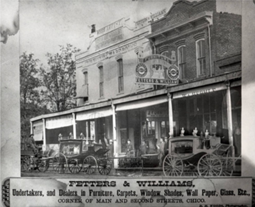

Now Emalyn is mourning both her son and her mother, and a double funeral is now underway. The funeral is held in Chieco at Fetters and Williams (both a funeral parlor and furniture dealer) pictured above.

In May 1913, the local newspapers report that Emalyn is in Chico, in the care of a physician.

But the year is not yet over.

Not even two months after the death of her son and mother, on June 9, Emalyn’s husband John Burney is killed in an accident.

What seems to have happened was this. John had recently purchased either a new vehicle or a new piece of mechanized farm equipment around the beginning of June. Around 9pm on Sunday night John, along with a hired ranch hand named “Red” or “JJ” Morgan or Martin (accounts differ on his name) was going home from Butte or the Baker-Shaw Ranch (accounts contradict the direction). They had been travelling about 30 miles per hour (ca. 48 km/h), when the wheels of the vehicle missed the bridge (the Sprague Bridge, five miles north and 18 miles (ca. 29 km) west of Butte City, near the W W Ludy Ranch) and the whole thing “turned turtle”. The field hand was able to leap free prior to the vehicle landing ten feet below, but John was caught beneath it. “Red” then ran over to the nearby Couch Range to get help, but — according to some accounts — found John already dead.

Once again Dr. Gatlin was called to the scene and, later, the coroner deemed the death accidental.

John’s last words were:

“For God’s sake get it off me. It’s killing me”.

One puzzling note is that one newspaper reported that John was survived by six (!!) children, his wife, and his mother who lives in Quincy.

Emalyn is back at the Marvin Chapel cemetery, final resting place of her father, her mother, her brother, two of her children and her husband — all gone in the span of ten years.

All that remains of her family is her eldest son, Royden or Royd E. Burney, born in 1906 and now about six years old.

Not much information is readily available pertaining to John Burney’s and Emalyn’s situation, but the last census from 1910 indicates that they are living in a rented or mortgaged farm. Emelyn’s mother is living with them.

There are no extant records of Emalyn’s marriage to John, but presumably they were wed between 1904 and 1905. John, as indicated earlier, is a bit shadowy and records about him are sparse. How they met is impossible to determine from the records. Had they known one another prior to the death of Emalyn’s father? Did John farm nearby or was he working in Quincy? Did Emalyn marry for love or was expediency driving her?

Here seems a good place to explore the name “Royden”. It’s an old English place name, usually a surname, meaning “growing with rye on a hill”. It’s a very old name, originating from Essex, Norfolk, and Sussex. Interestingly, there doesn’t appear to be any forebears on either side of the family with the name “Royden”, and yet there must be some reference as it is not a particularly popular given name.

In any case, it seems that Emalyn’s financial situation became even worse than before. Things were so bad that she gave up her son to an orphanage in Vallejo raise him. It seems that not even John’s mother was willing or able to help Emalyn or young Royd.

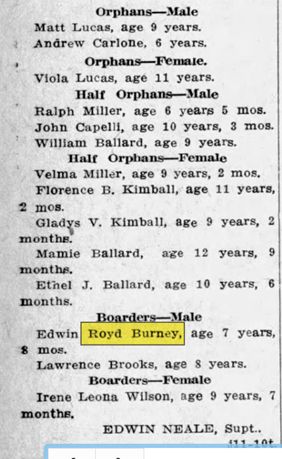

According to newspaper notices, “Edwin” Royd Burney, age seven years and eight months, was admitted as a border to the Good Templar’s Home for Orphans in Vallejo California sometime between October 1 and December 31, 1913.

Emalyn had consigned her last child and blood family member to the International Order of Good Templars' Home for Orphans, located in Vallejo California just prior to Thanksgiving and Christmas 1913.

Another sad Christmas.

The Good Templar’s Home for Orphans, Vallejo California

The Good Templars Home was founded in Vallejo in 1869 and operated until 1919 or 1922, and it took in children from throughout the State of California, with the majority coming from the northern part of the State. After it closed, the grounds became a golf course, and in the 1930 a subdivision called “Vista de Vallejo” was built on the nearby hilltop.

Not yet known for scandal, in November 1910 the Vallejo Evening Chronicle described what would be viewed as a sumptuous Thanksgiving dinner prepared for the Home’s residents. The paper reported that the affair:

…was well worth looking upon. The heavily laden tables were covered with snow-white tablecloths and spread upon them was a wealth of roast turkey, cranberry sauce, fruit, candy, cakes, pies, and other good things. There was an abundance of everything; two huge turkeys being set aside to be used later. The Home contains 112 children at the present time and every one of them was made happy… through the generosity of our people. Those having charge of the arrangements for the dinner desire to thank the employees of the Mare Island Navy Yard and the people of Vallejo for their liberality.

What began in New York in 1851 as a temperance society, the Order of Good Templar’s bough 103 acres of land in 1867 from the son-in-law of General Mariano Vallejo and began building the three-story mansion in 1869. The grand opening took place on October 1, 1870 and by the end of 1871 more than 100 children had been admitted to the institution.

Over the course of operation, the Home would take in more than 4500 boys and girls, ranging in age from 18 months to 16 years. Some children were fully orphaned (both parents deceased) or “half-orphaned” (only one parent deceased), along with boarders (such as Royd) whose parents found themselves in financial straits. In addition to these benevolent activities, the Home also busily acquired more land, which enabled them to create a prosperous farm which included livestock, a dairy, trees, vegetable gardens, along with wheat and hay fields. By 1872 they had opened a school which expanded in 1881.

Supported financially by frequent and substantial donations, the Home assigned chores to the children, provided Sunday school lessons and church services. The children were also allowed to attend community events and even had free admission to a local movie theatre.

In 1899, an official report on the school maintained that the children were “all well and happy”, management was “good” and as there was the expectation that donated farmland would be added to their holdings, the whole affair would be debt free. By this time there were about 200 children living there.

But, to the disappointment of management, the land transfer was delayed, donations dwindled, and over several more years the number of children there dropped to just a little over 100. By 1908 they were more than $15,000 in debt, buildings were dilapidated, and sanitary conditions deplorable. Management oversight was deemed “lax”.

One change later that year was to name a new superintendent, W.H. Dunning. Then, in August 1909, Dunning ended up in jail, accused of “lewd” conduct with about one dozen boys. Two months later he went to trial. Dunning was convicted and sentenced to 30 years in San Quentin Prison, but, then as now, he was paroled much sooner, in July 1917.

The directors then assigned Edwin Neale as superintendent, and this is when Royd was sent to the Home.

Not to get ahead of the narrative, but after the scandal involving Royd (and others), Neale was determined incompetent and was forced to resign (seemingly because the State threatened to cut funding unless he was replaced).

To wrap up the background on Neale, he did stay in the business (so to speak) and in March 1915 he opened the Vallejo Boys’ and Trade School (on what is now Broadway Street). A much smaller school, he poached several boys from the Orphanage, which by 1920 no longer existed. His wife, who worked with him at the Orphanage, divorced him.

To conclude the background story on the Orphanage, another superintendent, Fred. G. Anthony was arrested in March 1919, this time for lewd conduct with girls. He, too, was found guilty and sentenced to prison at San Quentin.

By the middle of 1919 only 27 children remained at the Orphanage, and the directors decided to shut everything down. But the institution still made news in 1921, when Anthony got an appeal and a split California State Supreme Court decision for not having received a fair trial.

The issue centred around Antony having been accused of lewd and lascivious conduct with a twelve-year-old girl, but the Solano County District Attorney, Arthur Lindauer, brought into evidence other sex crimes that Anthony had not been charged with. Lindauer questioned Anthony about why he did not mention a room where he had raped and nine-year-old and a thirteen-year-old girl. The question implied that Anthony was a rapist and was therefore prejudicial.

The case was dismissed in May 1922, after the girl who originally testified against him refused to take the stand again. She further stated that she never heard of Anthony, did not remember the twelve-day trial in 1919. Other witnesses from 1919 could not be located.

Anthony was then a free man.

In 1923, the orphanage was rented to the Vallejo Mare island Golf and Country Club, but the mansion was torn down after the Golf Club moved. By the 1930s, homes were built on the property.

All that remains of what once was is an underground cistern and some rubble from the original concrete foundation.

There is also an old mulberry tree remaining, the last living thing from the time before when the orphanage grew 100s of fruit and walnut trees. Perhaps Royd and thousands of other children sat under its shade in the California sun, eating the ripe berries as they fell on the ground below.

A Very Bad Year (1914)

Emalyn became elusive in 1914. After consigning her son Royd to the orphanage, she only appears once in print before the next tragedy unfolded. The Oroville Daily Register, Wednesday, September 16, 1914, informs that: “Emalyne R. Burney (‘of Chico’) is a visitor in Oroville”.

A mere four days later, the mutilated and nude boy of eight-year-old Royd, who had been missing for thirteen days was found an attic crawl space of the Good Templar Orphanage.

After September 1914, Emalyn starts to disappear from the records. It is its eerie stillness, as if life had been stopped in mid-breath.

Only two more references are made to her specifically:

- Vallejo Tribune, Monday, September 21, 1914, which wrote that Emalyn “arrived in Vallejo from Chico Saturday afternoon, took charge of the remains, which were shipped to Butte City where the funeral was held yesterday.”

- Oroville Daily Register: On September 22, 1914: “Unable to maintain her home, Mrs. Burney went to live with her mother-in-law in Nevada.”

The Burney Women — and The Elusive Mother in Law

These are steely-eyed women indeed. Aside from a clear facial resemblance, note the wagon-wheel hair clip that both sported.

The Murder Most Foul of Young Burney — and the Cover-Up

It was a Saturday afternoon at the orphanage on September 5, 1914. Little Royd Burney, described as a bright, mischievous, cheerful and healthy youngster. His nickname was “Little Red Head”; he had a shock of red hair, and was the only child in the orphanage with that hair colour. He was further described as being “well-built” for his age — 8 years old at the time.

That afternoon Miss Jessie White or Farley (records differ on her surname), matron of Royd’s dormitory (located on the third floor), had shooed him and the others to play outdoors. Royd and his friend, Clyde Harvey (see footnote #1), raced for the swing. Royd lost the race and went back into the building by way of the back stairs for a drink of water.

Royd was not seen alive again.

His absence was first noticed by Jessie around 4pm, at dinner time. Superintendent Edwin Neale was advised, but showed no pressing concern, stating:

He’ll come home when he’s hungry.

Later that night a cursory search was made within the orphanage (the girls' area was not included) and Neale did put out word to local ranchers and the police.

Jessie White had only been in Vallejo for four months, having been previously in Chicago. When called on to testify she added that some of the smaller boys thought Royd might have gone into the “slips” where he had been found on a previous occasion. She characterized Royd as being “unusually bright”, inclined to being mischievous, and generally quite a happy boy.

Royd had been in a few scrapes before. In fact, the Thursday before his disappearance he had been sent to bed early as punishment for climbing out onto the institute's roof. Perhaps Royd's history (wandering off to the "slips" — whatever that was — and going up to the roof) contributed to the initial unconcerned attitude of Superintendent Neale.

Thirteen days later, on the September 18, a horrible stench was emanating from an attic crawl space behind and above the girls' wardrobe room. A workingman named Harry Cook crawled into the space, where he found a pair of tiny overalls and an unions suit, both of which he threw out behind him. He raised a light to peer more deeply into the space and cried “he’s there!”. What he found was the naked body of Royd, lying on his right side with a pillow under his head.

Others went into the space. Royd’s body was resting upon the hard plaster between the laths of the ceiling. It appeared that the body had been dragged into the space, and another worker, Charles Dutreaux, noticed a protruding nail where he retrieved 10 small red hairs.

Superintendent Neale, now in full damage control, opined that the boy was “venturesome”, had probably crawled into the space, found himself trapped and afraid. Neale then surmised that Royd took off his clothes, laid down on the plaster and went to sleep. Once Royd awoke in the dark, he became afraid and died of a heart attack due to heart disease. He also went on to say that Royd’s mother, Emalyn, had taught her son to strip himself naked before going to bed, which was why the boy was found naked!

Neale was apparently schooled in the “let’s blame the victim” theory, but that notion did not find many supporters in Vallejo.

In any case, a coroner’s inquest was called, and all witnesses were interviewed. The conclusion was that the death was due to a “cause unknown” and that further investigation was warranted.

Meanwhile, an autopsy was performed on young Royd’s body. Back in 1914 the science of forensics was nowhere near where is it today, but they were able to make some determinations despite the advanced stage of decomposition of the body. In fact, it was the decomposition that gave an indication that Royd had been strangled.

The conclusion reached by the coroner was based on the fact (or theory) that where the skin is broken decomposition will be more rapid. Royd’s skin was, for the most part, intact everywhere except around the neck and the left side of his face where there was an indication of rapid decomposition. It was further theorized that the broken skin was the result of a strong person choking the boy.

District Attorney Joseph Murray Raines (1879-1964) would be tasked with proving this theory. And also finding the guilty party.

The Rafters

The hole that led to the space between the rafters and the ceiling originated in the girls' wardrobe room, a place where their best Sunday dresses were stored.

This access had been created by electricians years prior. It was four foot high and was located above a dining room. Boys were not allowed anywhere near this area, and the room through which one could access the hole was always locked. Only one key was known to exist for this room, and it was kept by Mrs. Birdie Gall, the girls' matron. The only other way into the space was through two windows.

Jessie White (or perhaps Jessie Farley — the records are conflicted) later testified that the area of the wardrobe where the hole was located had been searched at least three times since the moment of the disappearance.

Various pieces of information did surface during testimony by individuals summoned by the coroner B.J. Klotz and which was held (oddly) at McDonald’s undertaking parlour. About a dozen persons were called to testify, some of whom contradicted each other.

Another key witness, Mrs. Bertie (or Birdie) Gall (or Galt, depending on sources) was the girls' matron and her offices were located on the second floor. She was on the stand for a very long time, particularly when she testified that she burned the Royd's clothes and the hair that had been found in the area because she thought the authorities had already examined them.

Next to testify was Superintendent Edwin Neale. He reiterated that from the start he believed Royd had run away or had been kidnapped by “hoboes”. He emphasized that he had done the right thing by alerting nearby ranchers, police, and a probation officer named Kelleher to search, particularly in the area of Lake Chabot.

Next up was Dr. E.A. Peterson who performed the autopsy. It was he who identified the rusty nail with red hairs belonging to Royd. There was also a small spot of blood on the nail, which Peterson identified as human. No other blood was found.

Neale's wife (who later divorced him) was asked to testify, but she declined stating that she had only been associated with the Orphanage for two months and had been out of town the Friday preceding the disappearance of the boy. She did however state that only she and Birdie Galt (or Gall) had keys to the area in question and that she had left her set in the office while away.

Charles Dutreaux

Further details were provided by Charles Dutreaux. It was Charles who noticed the nail with “several” strands of red hair and marks of blood on it. Charles and Harry Cook (more on Harry later) had been in area of the second floor on Saturday around 4pm, but he claimed he would have heard something had anyone gone through the room. He further testified that he, Cook and a laundryman named Joe Veracruz were the ones who noticed the foul odour emanating from the hole. Around the time they noticed the smell, Superintendent Neale appeared and asked “What’s all the excitement about?”. The three men explained and Neale said “make a thorough search, boys”. He then described how Harry Cook found the body and how he, Dutreaux, had been previously unaware of the opening.

But there is more to the story of Charles Dutreaux (he is sometimes referred to as Charles Dutro). In November 1914 (described as an employee of the Orphanage, but he may also have been living and working part-time as a painter in Solano as records from 1900-1916 seem to attest, and based on details from a near fatal automobile accident in 1912) he was held in jail, accused of “contributing to the delinquency of a minor female”. The newspapers at the time speculated that there was strong evidence against him and that he would likely be sent to San Quentin to join the former superintendent (see above) W.H. Dunning for what the papers called “unprintable” crimes.

What brought Dutreaux to this point were the comments made by some children and led authorities to believe that he was responsible for the abuse of several young girls by “certain employees”.

One of the victims was a thirteen-year-old girl named Loretta Wilder. The encounter was witnessed by another youngster named Eleanor Green. Superintendent Neale, as would seem to be his habit, immediately blamed the victim, stating that she “had been in trouble before”.

But let’s see what else happened in 1914 to Charles. On December 27th he is given “emergency” clemency through the efforts of the Justice of the Peace, Berry Gregg (who also happened to be his lawyer), so a marriage can take place. The bride is a 20-year-old girl from Pinole named Margaret Van Proyen (or Van/Von – Proozen, Prooyen, Proyem, or Boryen, depending on the sources). According to Gregg, Charles and Margaret had been “dating for some time” and that the bride-to-be will “make an honest man of him”.

Margaret had already been married in 1907 (at age 17) to a certain Louis Wishaar, a 20-year-old man from Giant. Sometime before 1920 Margaret changed her name to Kathryn (although she sometimes spells her name as Catherine, which was the name of her sister) and married a man named Hurst.

There is no record of Margaret/Kathryn ever having married Charles.

In 1956, we find Charles again, this time in Concord California and charged with drunk driving and violation of probation (for a previous drunk driving charge). He didn't stay at the scene of the accident, but fled and was caught shortly afterwards.

In January 1964, Dutreaux and his wife had been babysitting two small children in their “low-rent” apartment in Pacheco in the Mount Diablo (!) area. The children were three-year-old Michael Domingues and his sister, a two-year-old named Debbie. The two children had been sleeping together on a couch in the living room of Dutreaux and the young girl was found dead. The brother was taken to hospital for observation, but was found stable.

The children had been left there two weeks prior, and Dutreaux explained that both had diarrhea the day before. He had checked on the children at 3am, found them fine, but by 5am the girl had died. Dutreaux's (likely second) wife, Louise Ann (age 55) commented that Debbie “was not feeling too good — you know how kids are”. At the time, the grandfather (Fred Trujillo, b.1919), of the children — who, incidentally, was jailed in Tulare County in 1940 — had been living in an apartment adjoining that of the Dutreaux's. The mother, Juanita Naomi or Neomie Trujillo (b. 1940) was a resident of San Francisco and worked at a department store. The father, Samuel Domingues (b. 1938), was with the US Army, stationed in Hawaii. They had married in September 1959.

To further document this little girl, she was born July 4, 1961 as Deborah Anna Dominguez or Domingues (spelling varies depending on the sources) and died on January 27th, 1964, and finally buried in the Golden Gate Cemetery of San Francisco. The medical examiner charged her father, Samuel, $295 for his services and, poignantly, on the documentation there is an instruction to comb her hair straight and not to make any curls. Her mother is not mentioned on the tombstone, but her father is.

In March 1964, once again in Concord, Charles applied for a license to sell beer.

And then Charles disappears from the record.

Emalyn's Trail Goes Cold

No one was ever convicted of Royd's murder.

His body was so badly decomposed that a coroner’s jury was unable to determine cause of death. John Neylan, chairman of the state Board of Control, said the boy was killed, but investigators were unable to develop enough evidence to file murder charges against anyone. Neylan also said the home’s superintendent, Edwin Neale, was incompetent, and the orphanage ran the risk of losing state funds unless he was replaced.

Neale resigned under pressure, but, as mentioned earlier, he continued to ply a living with orphaned children.

Emalyn became elusive beginning in 1914. After consigning her son Royd to the orphanage, she only appears twice in print before the next tragedy unfolded.

We find Emalyn in Chico on May 2, 1914 in the “care of a physician”.

The Oroville Daily Register, Monday, September 14, 1914, informs that: “Emalyne R. Burney (“of Chico”) is a visitor in Oroville).

A mere four days later the headlines screamed: “The mutilated and nude boy of 8-year-old Royd, who had been missing for 13 days was found an attic crawl space of the Good Templar Orphanage”.

Emalyn had lost everything. Her parents, her sibling, her home, and all her children. Her extended family of uncles and aunts are no longer in touch. Likewise, her in-laws appear equally uninvolved.

She was alone.

And so the sky hums with songs no one remembers.

After September 1914, Emalyn began to disappear from the records, with an eerie stillness, as if her life had been stopped in mid-breath.

Only two more references are made to her specifically:

Vallejo Tribune, Monday, September 21, 1914, which wrote that Emalyn “arrived in Vallejo from Chico Saturday afternoon, took charge of the remains, which were shipped to Butte City where the funeral was held yesterday.”

Oroville Daily Register: On September 22, 1914: “Unable to maintain her home, Mrs. Burney went to live with her mother-in-law in Nevada”.

Only there is no mother-in-law to be found. There is no census return, no property deeds, no wills, no probate… nothing. There is no evidence whatsoever that Emalyn went to Nevada. Her mother-in-law likely lived on the Nevada-California border, but even the California records are silent.

The Old Woman on the Milk Carton

Did she live on?

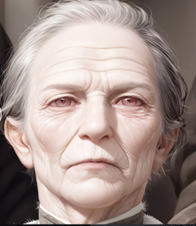

Below is an artificially aged picture of Emalyn which imagines how she might have appeared in old age:

Did she change her name? Did she remarry? Did she die alone and unceremoniously laid in a pauper's grave? Or did she re-invent herself and go on to live a happy life?

And so the sky hums with songs no one remembers.